How do urban poor make financial decisions?

Uncovering the financial behavior of urban poor households

This post is a summary of the report ‘Financial lives of urban poor households’ published by Bharat Inclusion Initiative and penned by Monami Dasgupta. You can check the full report here

Financial inclusion is defined as access to affordable banking services, credit, insurance and other financial products, regardless of economic or social status. Financial inclusion empowers people to escape poverty thus giving them a better life.

Government introduces a plethora of schemes to achieve financial inclusions. Most of these schemes are designed to accommodate the rural poor and are being retrofitted to the urban poor households.

But who are this urban poor?

The rapid expansion of cities has created an opportunity for low-skilled and migrant labour classes. Their services are usually cheaper and can be retained without providing appropriate compensation and social security. They end up living in slums and informal settlements around the city and are at risk of eviction and homelessness.

Non-contractual informal jobs (gig economy), volatile income flows, low ownership of physical assets, non-homogeneous social groups, and greater incidence of crime are a few of the challenges faced by the urban poor. Many urban poor households are headed by women, who often lack the resources and support to adequately care for their families.

In short, finding affordable housing with decent sanitation facilities and jobs that can sustain their daily life without harm is challenging.

I once interviewed a migrant Pan shop from Bihar who had set up a small shop in Bangalore. In the early days, he had to face drunk customers who would flee after buying cigarettes from him. As he neither spoke Kannada nor had many friends nearby he couldn’t avoid these incidents. He made it a point to form allies in the neighbourhood who would stand by him during such times. Lack of dignity and social status is a common threat for migrant labours moving to cities.

Table of contents:

To understand the financial lives of the urban poor, this study analyses data from 230 households across four slums in Chennai. The households were interviewed every 15 days for a year (Feb 2019 - Feb 2020) with the same questionnaire to understand their behaviour over a period of time. The respondents for these interviews are primarily women, as they take important financial decisions in the household.

Access to financial institutions:

In India, almost 80% of adults have a bank account (Thanks to the PMJD yojna scheme) Yet, the bank is not a welcoming place for the urban poor. They feel intimidated. Moneylenders and shopkeepers often act as financial advisors and provide them with credit. This informal system of credit is often expensive and exploitative. The poor have little or no negotiating power and usually pay high-interest rates. The urban poor also has to contend with the rising cost of living. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of their wages and makes it difficult to make ends meet. The increasing cost of essentials such as food and housing makes it hard for them to save money.

The respondents of the interview were able to name an average of 15 money lenders around their area whereas most were able to name only 4 formal financial institutions around them.

Awareness of moneylenders

Occupation:

The jobs undertaken by the survey households were low-income and low-skilled. The household occupations are categorised into wage, self-employed, building, and retail services. Members from the same household were engaged in jobs across all categories.

From the report:

We found that a higher proportion of older household members (member 1 and 2) are inclined to take up wage work, while the younger members of the household opted for both self-employment and wage work but have completely opted out of construction work.

Assets:

Most households were permanent residents in their location but had built their homes on encroached public lands or existing slums.

Possession of physical assets indicates the household's wealth and acts as collateral to borrow money during critical times. Assets like two-wheelers enable economic mobility. Gold is the most common high-value asset owned by households.

Gold is considered a highly liquid asset. They provide a hedge against inflation and empower women in the household to take independent financial decisions. Ownership of gold is usually higher in families with more female members.

Income and expense flow

Interesting observations from the graph:

Feb’s second fortnight has the lowest income

September’s first fortnight has the highest income as most of them receive a bonus for the festive season.

There is a constant dip in income from May to June. The hypothesis is that the steep rise in temperature would have forced the men to stay at home even if it means losing a day’s wage.

The spike in expenses during February and October is attributed to the wedding and festival seasons.

Weddings are usually frequent low events but are expensive ones. On average, households spent around Rs.8800 per event. Here is the breakup.

The households spend anywhere between Rs.1000-Rs.4000 per month to repay their debt.

Out of the 12-month survey, the households were in a net deficit for 4.5 months (i.e.) the expenses were more than the income.

Savings:

Bank accounts, chit funds and post offices are some standard instruments households use to save their money.

Chit funds enable households to build a substantial corpus by investing a small amount monthly. A common form of chit fund is a jeweller chit fund, a savings scheme that runs from October to September. In this scheme, the women systematically invest money for 12 months and are eligible to buy a gold coin or jewellery during the festive season. The women were reluctant to disclose their investment in these schemes as they are usually hidden from the family members. They could invest anywhere between Rs.200 to Rs. 2500 monthly in a jeweller chit fund.

Credit:

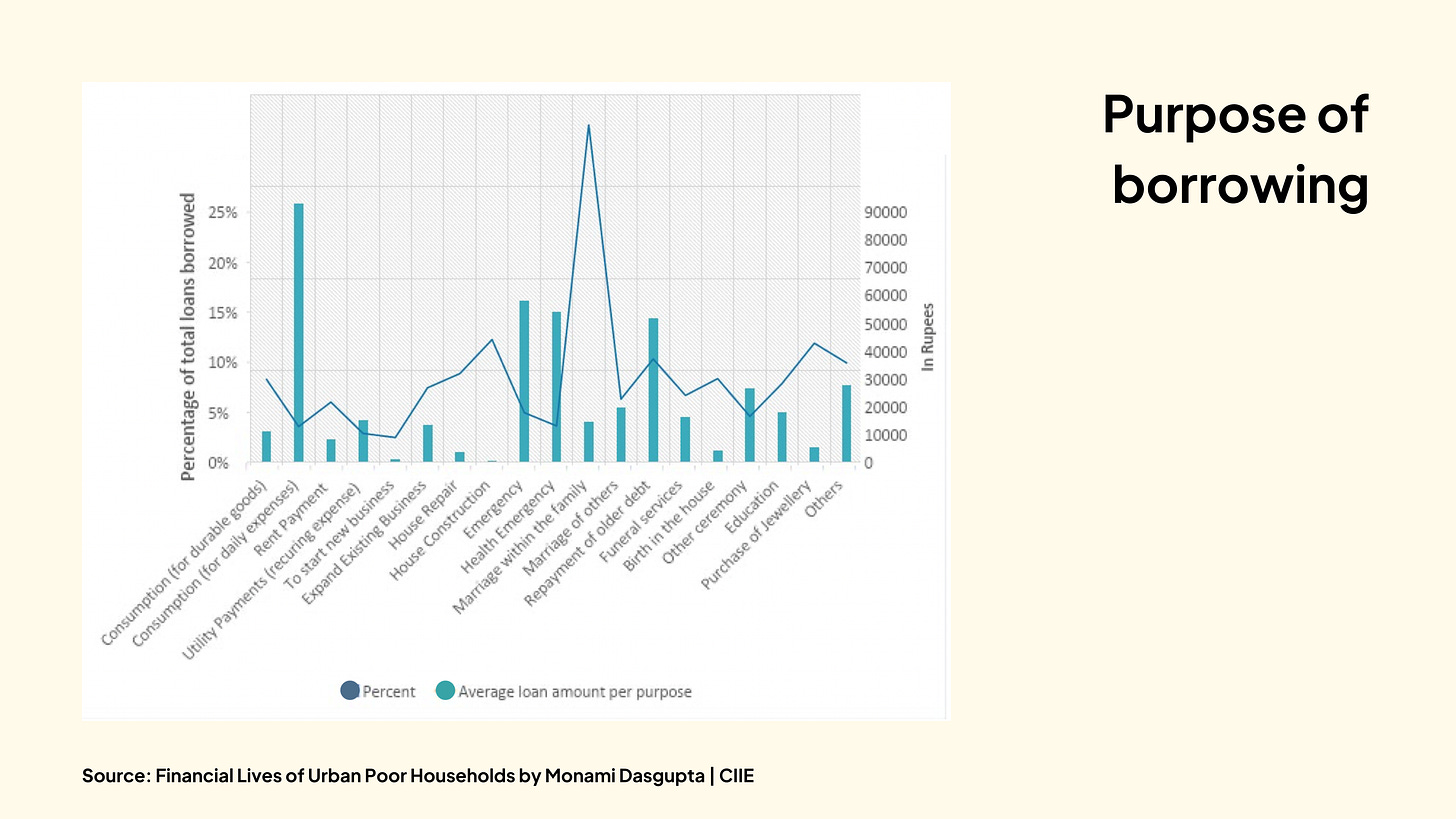

The survey respondents have high-cost informal debt, usually from a money lender. Some of these loans had been carried over for multiple years with cumulative interest. These loans are borrowed for consumption, health emergencies, education-related or to repay older loans.

Moneylenders are easy to access and can offer the required amount with convenient repayment schedules.

Households migrate to cities hoping for new life and better social status, but this comes with challenges. The report covers deeper topics around sustaining emergencies and remittances. The journey to understand the Indian land space is challenging, and the report gives us a comprehensive view of a particular section of society. Go and read the report.

This post is a summary of the report ‘Financial lives of urban poor households’ published by Bharat Inclusion Initiative and penned by Monami Dasgupta. You can check the full report here

Subscribe to 'The India Note' for weekly discussions on consumer behaviour in India.