India's lesser known Goldmines!

Masala movies, South India and YouTube

Welcome to the new 450 curious minds who’ve joined us since the last edition. If this was a forward, you’re welcome to join 17,655 VCs, founders, and product operators by subscribing to The India Notes. 👇

Beyond the newsletter, I run 1990 Research Labs, helping global tech companies and Indian market leaders truly understand consumer India. If you’re navigating an Indian consumer bet, let’s talk.

Most people think Baahubali made North India fall in love with South Indian cinema. They’re wrong.

A YouTube channel did.

I’m one of those people who watch more filmmaker interviews on YouTube than the films themselves. If you are like me, who binge-watch film critiques like Anupama Chopra and Baradwaj Rangan, then you’ve heard one term screamed across the film industry for the last five years now: Pan-India. The irony is that no one knows what it really means. Does it mean stars from across India? A film dubbed in multiple languages? A story with a nationwide appeal? Maybe it’s a bit of everything. Just like the Indian masala.

But one thing is clear, the Hindi-speaking audiences have opened up to watch commercial South Indian movies in theatres in the last decade. Interestingly, in 2021/22, for the first time, the gross revenue of all the South Indian movies (including Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada) exceeded the Bollywood revenue. We got some monstrous hits like RRR, KGF: Chapter 2, Pushpa: The Rise, Kantara. Each of these films did an upwards of 500+ crores in box office collections. Now there is also a term for these mega hits called ‘The 1000 crore club’.

Nine films in India have crossed the 1000 crore club, with Dhurandhar being the latest entrant. Out of the nine, five of those films are from South India and, to be specific, from the Telugu industry.

When you trace back to the origin of the Pan-India phenomenon, most would point it to the obvious name: Rajamouli, who is the director of the Baahubali series. While Baahubali did dominate the Hindi heartland, there is another quieter force who gets rarely mentioned: Manish Shah. You have probably never heard of him. He is neither a filmmaker nor a famous producer nor a hero. Yet he may be one of the most influential architects of this Pan-Indian movement.

A quick note before we begin. This piece will have a hero entry, jump cuts, sad moments, and unexpected twists. Why not? It’s a newsletter about South Indian masala movies. You might as well read it like one.

Who is Manish Shah?

When Rajamouli was on a trip to explore locations for the film RRR, he observed that Telugu actor Allu Arjun was a star in the North and had fans of his own. The crazy part is that Allu Arjun had never acted in a single Hindi movie. After returning, Rajamouli reached out to the director Sukumar and urged him to release his upcoming Allu Arjun film on a pan-India scale. Sukumar was hesitant, but Rajamouli persisted. He even personally spoke to the distributors to secure a wide release. Eventually, the film was released in Hindi with a massive launch and grossed over 300 crores, with nearly 100 crores from Hindi alone.

That film was Pushpa: The Rise. (Part 1)

Why is this story relevant? Because Allu Arjun’s popularity in the North can largely be traced back to a single YouTube channel - Goldmines. Manish Shah is the founder of Goldmines.

Introducing Goldmines

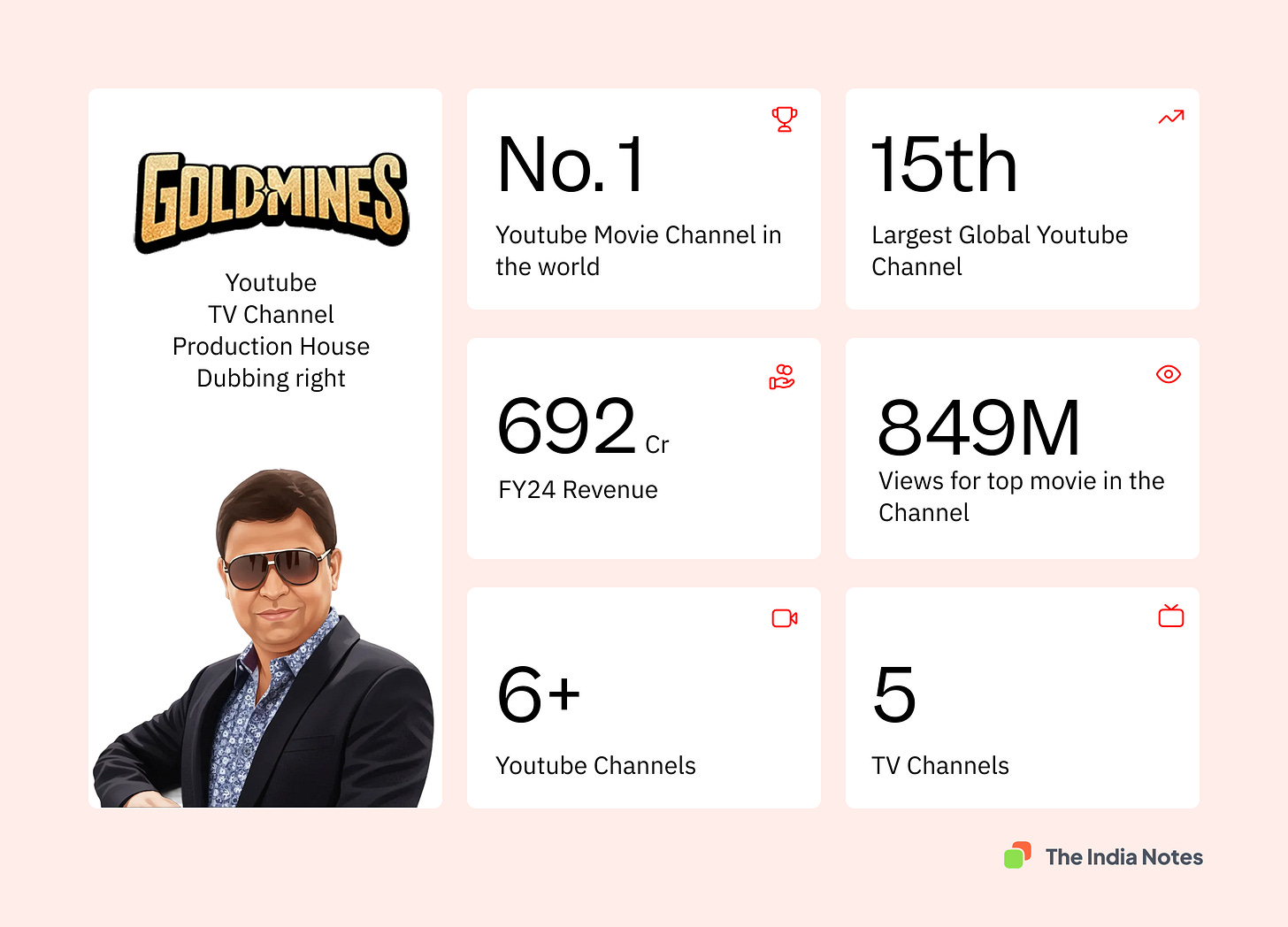

Goldmines is the go-to destination for South Indian films dubbed in Hindi. While the exact size of its catalogue isn’t publicly disclosed, it’s safe to say that no one else comes close. What makes Goldmines unique is how much it has built around a single IP: dubbed South Indian cinema. It operates across film distribution, production, multiple television channels, and an entire network of YouTube channels - all powered by the same core content.

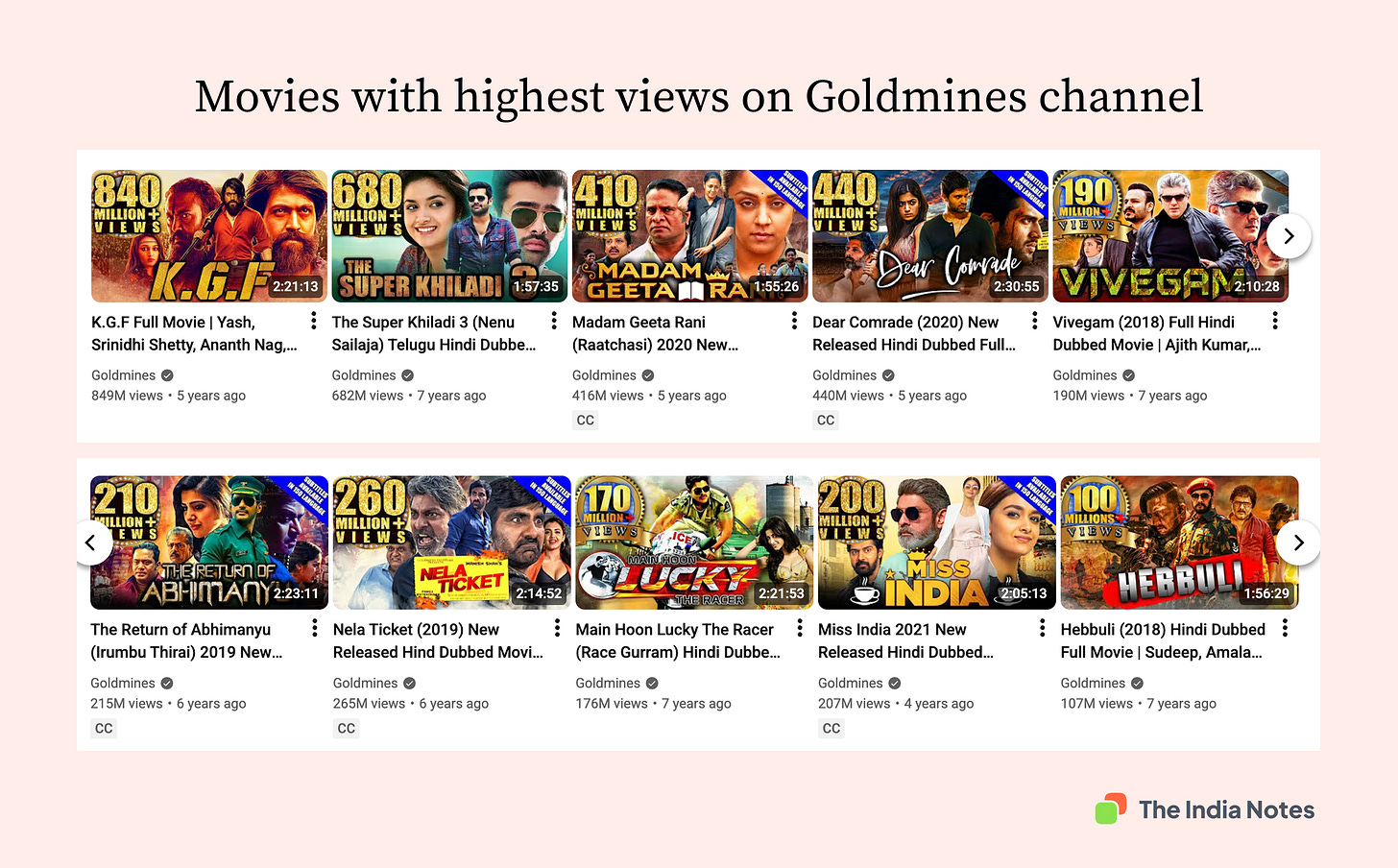

The flagship Goldmines YouTube channel isn’t just another movie channel. It’s the largest movie YouTube channel in the world and ranks 15th globally by subscribers, with over 108 million subscribers. The channel has amassed a staggering 31 billion minutes of lifetime watch time. Its most-viewed video - the Hindi-dubbed version of KGF: Chapter 1 - alone has over 850 million views. That number is almost hard to comprehend. And it’s not a one-off anomaly: the channel regularly hosts full-length films that cross the 100-million-view mark.

What makes this story even more remarkable is Goldmines’ origin. The company began in the early 2000s as a production house creating daily soaps for Assamese and Gujarati television. So how did it transform from a regional TV production company into one of the most influential forces shaping modern Indian cinema?

To understand that, we need to rewind a few decades - to the early 1990s. This story features Mani Ratnam, A.R. Rahman, and Roja.

History of South Indian dubbed movies

Let’s begin with Doordarshan (DD). By 1982, DD had introduced Sunday afternoon slots dedicated to regional cinema - Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Bengali films, often aired with English subtitles. For many Indians, this was their first real window into South Indian cinema.

Films like Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Elippathayam, Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan, and Girish Kasaravalli’s Kannada works introduced millions to cinema radically different from Bollywood. Doordarshan prioritized award winners and critically acclaimed. It framed South Indian cinema as “artistic” - and Bollywood as “commercial.” This distinction would stick for decades.

Meanwhile, distributors were experimenting with dubbing. In 1981, Rajinikath’s Tamil film Ranuva Veeran was dubbed into Hindi as Zulm Ki Zanjeer. It flopped. Through the 1980’s around 15-20 South Indian films got Hindi dubs and almost all of them failed. The reasons were consistent: poor dubbing quality, fragmented distribution networks and they couldn’t compete with Bollywood’s marketing.

Now in 1992, Mani Ratnam releases Roja. A film rooted in themes of patriotism and terrorism, paired with a groundbreaking soundtrack by A.R. Rahman that introduced a completely new kind of sound to Indian audiences. Recognizing its national appeal, Ratnam released Roja across India, but this time with a crucial difference: the film was carefully dubbed into multiple Indian languages, especially Hindi, with high-quality voice performances and culturally adapted dialogue. Roja became the first dubbed South Indian film to achieve genuine success in North India.

Roja proved three critical things: South Indian films could tell nationally resonant stories; thoughtful dubbing could preserve emotional depth; and pan-India releases made strong commercial sense. In many ways, Roja stands as the true precursor to the pan-India cinema movement we see today.

Satellite Channel Proliferation and Content Hunger

After India liberalised broadcasting, the mid-90s saw an explosion of private satellite TV. Channels like Zee TV, Star Plus, and Sony quickly launched 24x7 movie channels. These channels had a problem. They needed to fill 24 hours of programming every day, and Bollywood rights were expensive. Advertisers wanted fresh content. South Indian cinema offered the solution with a vast, untapped library. Initially dubbed South films were treated as filler for non-prime slots. But TRP data showed that South Indian dubbed films outperformed mid-tier Bollywood films, particularly among young male viewers in smaller towns.

Films like Indra: The Tiger (Chiranjeevi), King No. 1 (Nagarjuna), Aparichit (Vikram) developed cult followings through sheer repetition.

The great Bollywood disconnect

Now we arrive at Goldmines.

In the early 2000s, the rise of multiplexes like PVR and INOX pushed Bollywood toward urban, premium audiences, leaving behind the action-heavy, larger-than-life cinema that still resonated deeply in Tier-2 and Tier-3 India. While Bollywood evolved toward romances and urbane dramas, South Indian cinema - driven by stars like Rajinikanth, Chiranjeevi, and Nagarjuna - continued delivering mass spectacle.

Manish Shah spotted the gap.

His insight was straightforward: remove language and cultural barriers, and South Indian films could replace the kind of action cinema Bollywood had abandoned. By 2007, Goldmines had fully pivoted to Hindi dubbing.

The breakthrough came with the Telugu film Mass (2004), dubbed as Meri Jung: One Man Army. When it aired on Sony MAX in 2007, it crossed 1.0 TRP, a metric that denotes the movie as a superhit proving the model worked.

Goldmines then professionalized the space by acquiring 99-year Negative Rights, gaining complete control across TV, digital, and theatrical platforms. Unlike broadcasters paying recurring fees, Goldmines paid once - after breakeven, every rerun was pure profit. Long-term producer relationships and pre-buying rights sealed its dominance.

The value creation

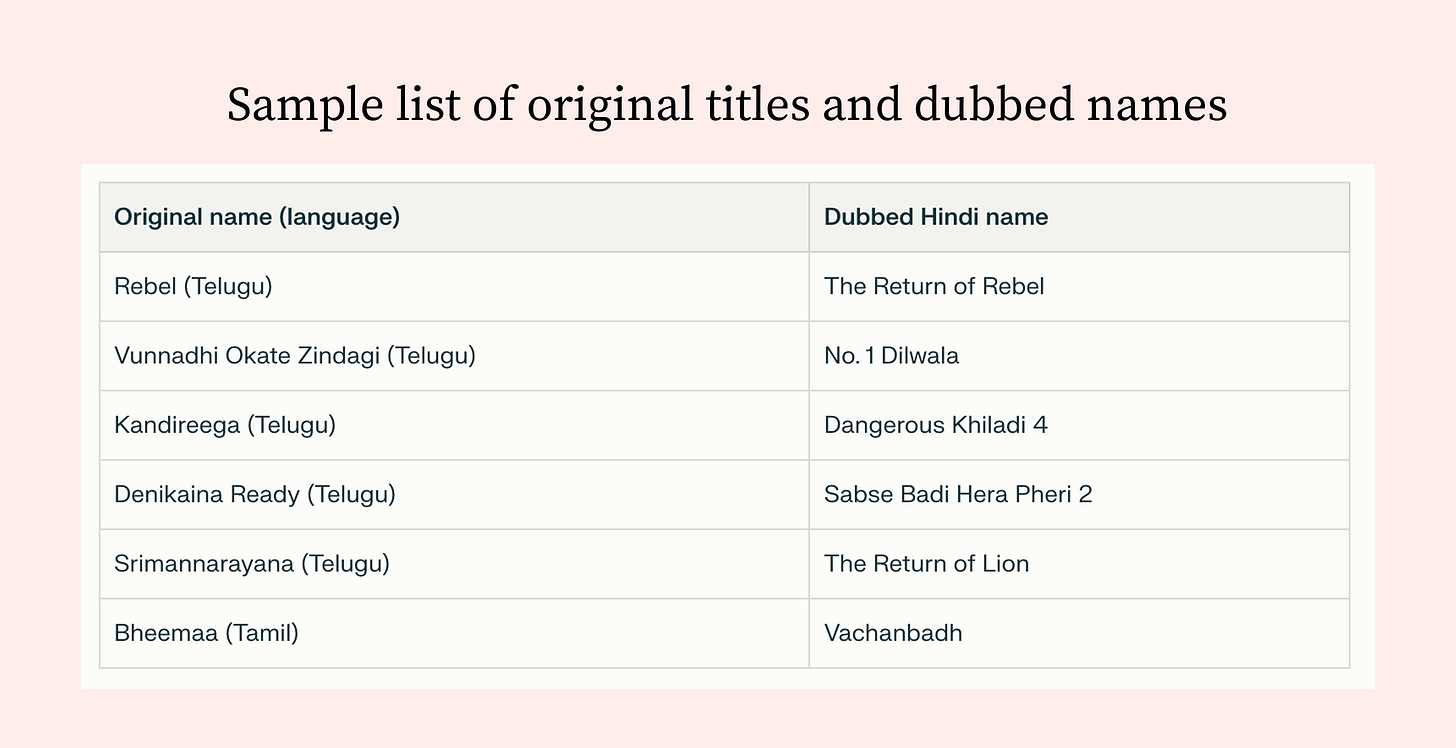

Goldmines didn’t just dub South Indian films. Manish Shah went a step further - he culturally adapted them. The goal was simple: make North Indian audiences feel like they were watching a native Hindi film, not a dubbed one.

This adaptation happened on multiple levels.

First: structural re-editing.

If a film ran close to three hours, Shah would often restructure it - reshuffling scenes so that every 15–20 minutes something compelling happened. This approach was initially driven by television logic: keep channel surfers hooked and prevent drop-offs during ad breaks.

A fascinating example is the Tamil film Anjaan, starring Suriya - one of Tamil cinema’s top stars. Released in 2014, the film came with huge expectations and a large budget but ended up as a major box-office failure, denting Suriya’s career.

Goldmines acquired the rights, but instead of simply dubbing it, Shah re-edited the film extensively - moving several second-half scenes into the first half to tighten pacing. When this version was released on YouTube, it became a phenomenal hit. Today, it has amassed around 84 million views.

The impact was so significant that the original filmmakers later released a re-edited theatrical version inspired by Goldmines’ cut. That’s the level of storytelling instinct - and audience pulse - Shah brought to the table.

Second: cultural sanitization.

Many South Indian films include rituals and social norms that can feel unfamiliar to North Indian audiences. For instance, in Tamil culture, marriages within extended family structures - such as marrying a maternal uncle’s daughter - are not uncommon. Similarly, there are elaborate celebrations marking a girl’s attainment of puberty.

These elements could feel alien or distracting to northern viewers. Shah would either edit such scenes out entirely or rewrite the dialogues to soften or reframe them so they didn’t feel jarring.

Humor received similar treatment. Comedy is deeply rooted in local culture, politics, and social context. Instead of literal translation, jokes were often rewritten to make them land naturally with Hindi-speaking audiences.

Third: lip-sync precision.

Goldmines paid close attention to phonetics, choosing Hindi words that roughly matched the original lip movements. The objective was to erase the “dubbed movie” feel as much as possible.

Finally: creative control through contracts.

Goldmines structured its legal agreements to allow these extensive creative modifications. This is why, even today, many films on YouTube list Manish Shah as a producer. In his mind, he wasn’t just dubbing films - he was reshaping existing artworks for a new audience.

The result?

A viewing experience where audiences often forget they’re watching a South Indian film at all. Combined with exclusive long-term rights, this gave Goldmines an unbeatable early advantage. Today, the company controls nearly 80% of the Hindi-dubbed cinema market, with a catalogue so deep and entrenched that it’s extraordinarily difficult to challenge.

YouTube Channel and TV Channel launch

Anticipating the shift to digital well before traditional broadcasters, Goldmines launched its YouTube channel in 2013. The strategy had two clear objectives: monetize its vast back catalogue through advertising and build a direct relationship with audiences, bypassing broadcasters entirely.

By 2020, the main Goldmines YouTube channel had crossed 42 million subscribers, generating meaningful cash flows and significantly reducing dependence on satellite rights. From there, the company scaled aggressively - expanding to 15 YouTube channels targeting different audience segments and collectively clocking around 100 million views per day across the network.

On television, Goldmines initially operated as a content supplier, powering channels like Sony MAX and Zee Cinema. But once it became clear that it was effectively building competitors on its own IP, the company made a decisive pivot.

In May 2020, at the peak of COVID-driven TV consumption, Goldmines launched its own free-to-air movie channel, Dhinchaak, on DD Free Dish. Within just three months, the channel surged from #5 to #1 in the Hindi Speaking Market, overtaking long-established giants like Sony MAX and Zee Cinema.

In April 2022, Dhinchaak was rebranded as Goldmines. Today, the network includes:

Goldmines - flagship South Indian dubbed blockbusters

Goldmines Bollywood

Goldmines Movies

Goldmines now consistently ranks among the Top 10 channels across all genres, topped the Hindi movie charts for 41 out of 53 weeks in 2024, and regularly outperforms Star Gold and Sony MAX - cementing its position as the dominant force in Hindi movie entertainment.

The rise in power

Great power comes with great responsibility but also controversy. Goldmines is no exception. While researching this story, two incidents stood out as particularly revealing of just how much leverage the company wields.

The first involves the movie Drishyam.

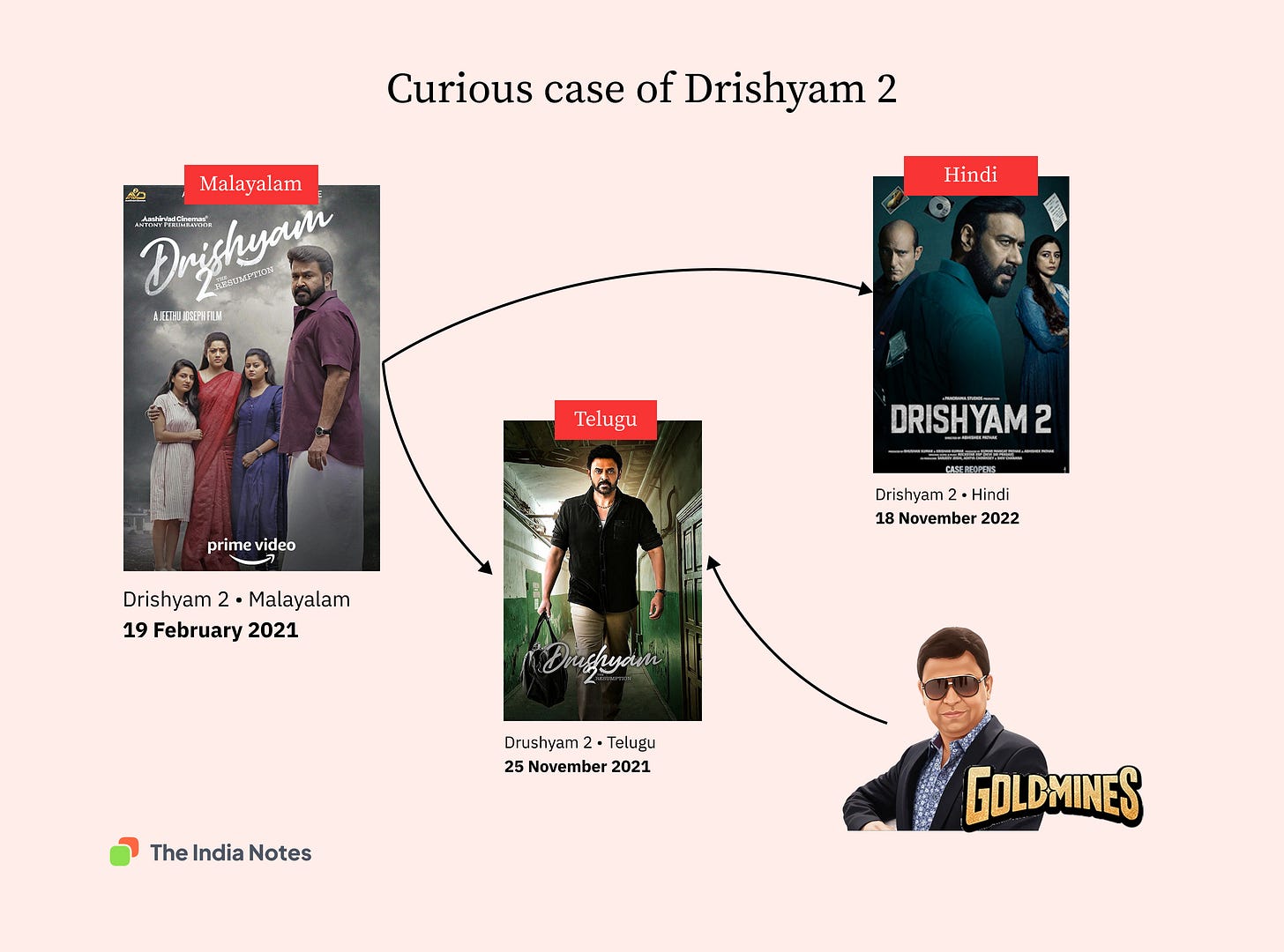

The franchise began in Malayalam and was later remade in Tamil and Telugu. Ajay Devgn acquired the Hindi remake rights and successfully released the first part Drishyam (2015). When Drishyam 2 became a massive hit in Malayalam, the Hindi producers again secured the remake rights from the original Malayalam producer for the second part.

What he didn’t anticipate was that Drishyam 2 had already been remade in Telugu, starring Venkatesh - and that Goldmines had legally acquired the Hindi dubbing rights from the Telugu producer.

In meanwhile Goldmines announced plans to release the Hindi-dubbed Telugu version of Drishyam 2 on YouTube before the official Hindi version. This posed a direct threat to the Hindi theatrical remake. Faced with this situation, producer Kumar Mangat entered negotiations and Goldmines agreed to hold back the YouTube release in exchange for ₹3.5 crore.

Manish Shah later confirmed the deal, framing it as a straightforward business decision - he had legally purchased the rights and was simply looking to monetize them.

The second case centers on Shehzada.

Shehzada, starring Kartik Aaryan, is the official Hindi remake of Allu Arjun’s Telugu blockbuster Ala Vaikunthapurramuloo. By the time Shehzada was in production, the Hindi-dubbed version of Ala Vaikunthapurramuloo was already available - and immensely popular - on the Goldmines YouTube channel.

Goldmines then took things a step further by announcing plans for a theatrical release of the Hindi-dubbed version. This sent shockwaves through the industry. Allu Aravind - producer of the original Telugu film and co-producer of Shehzada - personally reached out to Goldmines, requesting them not to go ahead with the theatrical release, fearing it would cannibalize the Hindi remake.

Despite the drama, Shehzada went on to underperform severely at the box office - a story in itself.

Together, these episodes underscore a larger point: Goldmines isn’t just a distributor or a dubbing house anymore. It has become a powerful gatekeeper in the North Indian market - capable of influencing release strategies, negotiating from a position of strength, and reshaping the economics of remakes and dubbed cinema altogether.

Moving forward

But not everything looks rosy for Goldmines today.

The very rights that could be acquired for ₹10 lakh a decade ago now cost upwards of ₹20 crore, and producers are increasingly reluctant to sign away 99-year negative rights. This shift poses a structural threat to Goldmines’ core model - and to Manish Shah himself.

Anticipating this squeeze, Shah has begun moving upstream into big-budget film production.

His flagship project is Kanchana 4, the next installment in the popular Tamil horror-comedy franchise led by Raghava Lawrence, and featuring Pooja Hegde and Nora Fatehi. The strategy is clear: own the IP from day one, across languages and platforms, eliminating dependence on external producers and future rights inflation.

Beyond Kanchana 4, Shah has also confirmed upcoming projects with major South Indian stars, including Sivakarthikeyan, Vijay Sethupathi, Mohanlal, and Dhruva Sarja. The ambition is to transform Goldmines from a bridge between industries into a full-fledged pan-India production house.

In many ways, this marks the next - and most difficult - chapter for Goldmines. Distribution and arbitrage built the empire. Original production will determine whether it can sustain one.

Conclusion

In the 1970s, Nestlé wanted to sell coffee in Japan. Japanese people had no coffee culture. When Nestlé hired a French psychoanalyst named Clotaire Rapaille to understand why their products weren’t selling, he discovered something fundamental: You cannot sell to a culture that has no memory of you. So Nestlé stopped selling coffee. Instead, they started selling coffee flavoured candy. For fifteen years, they planted the taste. Then, in the 1980s, those candy-eating children entered the workforce. Nestlé returned with actual coffee products. Today, Nescafé commands 70% of Japan’s instant coffee market.

Manish Shah did for South Indian dubbed movies what Nestlé did for coffee in Japan.

Goldmines didn’t just distribute films. It raised a generation with South Indian sensibilities. The question now is whether Shah can keep feeding that generation - or whether the taste he created will be satisfied by someone else.

If you liked this essay, consider sharing with a friend or a colleague that may enjoy it too. (If you share on socials, tag me. I’m on Twitter (X) and LinkedIn)

Shoutout to Raunaq Mangottil (Fully Filmy) and Pranav Manie (Hot Chips) for reading the preview and helping sharpen the edits.