Product Insights from Social Games, Cricket, and Payments

A conversation with Anshumani Ruddra, Product Leader for Google Payments

Today I have Anshumani Ruddra, who has more than 15 years of product experience across multiple companies like Zynga, Hotstar, and Google Pay. In this edition, I spoke to him about how he transitioned from gaming to entertainment and most recently to payments and the consumer insights around it. He’s one of the best product managers that I have seen with a great design bent in the country. I hope you get to take some interesting anecdotes and stories from it.

What did we cover?

A Career of “Side Quests”: Defining a career by its wandering paths, not just its titles.

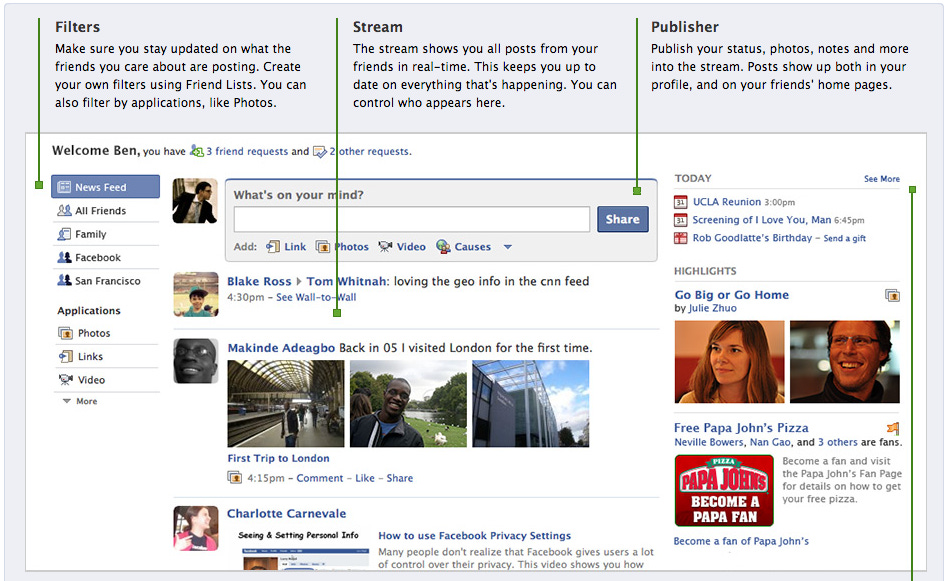

The Zynga-Facebook Era: A look back at 2012, when social gaming was the utility of Facebook for millions.

Platform Risk: How Zynga navigated its heavy dependence on Facebook and the difficult shift to mobile.

India’s Mobile Gold Rush: The challenges of building games when data was costly and APK size was a primary metric.

Virality as Delight: Why the smallest in-game action (the “dopamine hit”) was the key to user retention.

Reviews as Insights: How “ratings and reviews” served as the first line of qualitative feedback.

The Sports Bar on Your Phone: The insight behind Hotstar’s “Watch and Play” to capture the “armchair critic.”

Delight in Payments: Moving from games to payments, and the surprising importance of “delight” in finance apps.

AI’s Next Frontier: Why Generative AI must evolve from just “asking” (chatbots) to “doing” (agent-based actions).

A Career of “Side Quests”

D: I’ve known you for almost 10 years, and I somehow relate you more towards a designer who communicates through narratives than an engineer who communicates through numbers, despite your credentials. How do you see yourself?

A: Thank you for saying that. I’ve always thought of myself as a mix. I think people define themselves too narrowly, either by their educational background or by the work that they do. One has to keep reminding oneself that the title is given to you; you have to choose whether you want to accept it or not, and whether you want that title to define you.

I don’t necessarily recommend my career path to people. I took a lot of detours; my career path is not a straight line at all. It’s a wandering path. I’ve written about it: there are people who play the “main quest” in a role-playing game, very story-driven, where A leads to B leads to C. Then there are people who are like, “Oh, let me do all the side quests. I can go into this other part of this forest and meet some other creatures”. I’m a “side quest” person. I’ve realized that my entire career can be defined as this one giant series of side quests. But when you add them all up, there is progress, and it looks really good on LinkedIn or on a resume.

D: Can you trace that “side quest” path for us, from engineering to writing, gaming, and eventually payments?

A: I have always looked at these things as, “Hey, don’t allow yourself to be narrowly defined by the title that somebody else is giving you”. We may be naturally gifted at certain things, but then there are other things on which we spend a lot of time and build those faculties. I started coding at a very young age, but I also started writing at a very young age. I wanted to do computer science and engineering but got into chemical engineering. I actually fell in love with engineering, but only by the time I hit my third year of college.

As it was coming to an end, I decided I was going to sit and write full-time, because that brought me the most joy. Then gaming happened, which was also like, “Hey, I’ve always enjoyed playing games and designing board games, so let me get into digital gaming”. That led to healthcare, education, media, and payments.

Payments is very strange. My dad is a banker, so my childhood was spent discussing money as a very intellectual concept with him. It’s strange I ended up in payments because if you had asked me 20 years back, “Would you ever be in payments?” I’d be like, “Nah, that sounds boring”. As a kid, I thought my dad had the most boring job. Now I’ve been in payments for almost five years, and I think I’ve become a semi-expert. Life takes you on different paths. I’ve already had three or four careers. If I live to see 80 or 90 and health permits, I’ll probably have four or five more.

The Zynga-Facebook Era

D: You were at Zynga around 2012. Can you paint a picture of that time for an audience that may not remember it? What did Facebook, mobile, and gaming look like?

A: 2012 was a very interesting time. The iPhone moment had happened in 2008, but if you remember, the iPhone did not launch with the App Store; that came a little later, and it came prepackaged with some apps. In that 2009 to 2012 period, we all realized there was a very distinct shift from desktops and laptops to the mobile era. Mobile was going to dominate, and people would be carrying these incredibly powerful supercomputers in their pockets. People still thought certain things could only happen on a larger screen, and that work would not get replaced. It was also coinciding with the rise of WhatsApp.

For context in India, we were still on crappy 2G and 3G connections. Jio had not yet broken the dam of really cheap 4G connectivity; that happened in September 2016. So, data was very costly. While mobile phones were selling like hotcakes and more people were moving to smartphones, mobile data was still very costly.

D: What was the specific relationship between Facebook and Zynga at that time?

A: Globally, Facebook was evolving. Facebook and Zynga had both gone public pretty much back-to-back. There were very clear call-outs in each of their S-1 filings. Zynga had very clearly said that about 90% of its revenue came from Facebook as a platform, which is very large. In our filing, we had to declare the risk of this very heavy dependence on Facebook.

But people must remember, this was before mobile advertising took off and Facebook became an advertising giant. So Facebook also had to declare that most of its money was made from developers like Zynga. I would even extend that to say that for a lot of Facebook’s users at that time—Facebook might not like to admit it—its big utility for them was playing games. It was playing games like Farmville, Mafia Wars, and CityVille. These were among the first games to hit tens and 20 and 30 million daily active users. Facebook’s scale-up and its social graph’s usage were very, very dependent on large game developers like Zynga, and Zynga was the largest of all of these.

This part of tech history gets ignored. People who didn’t play games were always complaining, “My entire social feed is full of these people hurling sheep at each other,” or “My friends are like, ‘Can you send me this thing in Farmville?’”. But the reality was, for pretty much everyone else, their entire social graph’s utility was playing games, not liking pictures or writing on people’s posts. People made very significant connections. We used to hear wonderful stories, like grandchildren keeping track of their grandparents’ health because they all used to visit each other’s farm. So, if grandmom hadn’t harvested her crops, something was wrong. You’d need to call the old age home and say, “Hey, is everything okay? Because she’s not been active on Farmville today”.

D: You mentioned these games created real connections. Did you see that personally?

A: I was the design lead on Mafia Wars, and it was an insane community. People became friends with people. I was also a very heavy Clash of Clans player in its early years and could see that social narrative on the phone happening. I was playing Clash of Clans on the day I got married. I was playing Clash of Clans on the day my kid was about to be born; I was nervous and pacing outside. This group of strangers who used to be in my clan stayed up in different time zones with me when I was really nervous about my kid’s birth. I remember for my wedding, this group of strangers got together and sent me an Apple gift card. These are not friends. These are just people I play a game with, and they’d become good friends over time. This is the power of apps at that point.

D: What caused the shift away from this model, and where did the gaming world move?

A: These games mattered to people and were probably among the first games a lot of people played. But as Facebook started distancing itself from games, realizing a big chunk of its revenue was very dependent on them, it started doubling down on mobile ads revenue and building new revenue streams. Gaming on Facebook became a smaller thing.

It was very difficult for mobile gaming companies to then turn themselves into a destination. But we started seeing it with Angry Birds, or King.com doing really well with the Candy Crush saga series, and of course, breakout hits with Clash of Clans. You started realizing that these mobile apps are a destination in themselves. You were used to a mentality of being on top of another platform, which used to be Facebook, but now the platform became the App Store and Google Play Store, and you had your own apps people could directly interact with. That shift got people off guard. In 2012, I was in the middle of that shift. I could very clearly see mobile gaming was the future if I had to continue in gaming. And I could see the numbers in India changing. The Play Store had just launched; it was not yet a year old when I got into gaming and started setting up my game studio. That’s where the world was in 2012.

Platform Risk

D: You mentioned Zynga realized the heavy dependence on Facebook was a threat. When you moved to mobile, was there discussion that you were just trading one platform risk for another—the App Store and Play Store?

A: Zynga had some of the most strategically smart product managers; in a lot of ways, Zynga defined Bay Area product management in that phase. It was a very data-intense, data-driven way of looking at things, but also very strategic. Everyone was very clear that this was a very big danger. Zynga had spent a lot of effort turning zynga.com into a destination. It had also made fantastic acquisitions, like Words With Friends, which was one of the first breakout hits on mobile; Zynga purchased that studio and the “With Friends” franchise.

So it’s not like Zynga was caught completely unaware. It’s just very difficult when you have tens and tens of millions of users on one platform to suddenly tell your team, “Hey, web development is over, and now we are going to develop Android and iOS apps”. It’s a very difficult shift, and Zynga did do it, though we were slow. But so was everyone else. Any existing studio moving to mobile games took a while. People who were brand new studios, who started by saying “we will only build mobile games,” had a much easier time. Zynga was aware of the dangers of being overdependent and had already started hedging its bets, but this overall move took time.

Remember, the stock market is very narrative-driven. Zynga’s IPO was decent, but then the stock dramatically fell, and it took a long time for Zynga to recover. You could argue that Zynga never recovered, at least from that perception of being a market leader. But Zynga was a very hyper-profitable company. We used to make crazy amounts of revenue on the games we had; our user base and revenue were fantastic.

D: Were there any specific insights from how Indians were playing these Zynga games at the time?

A: We had very decent usage in India. Remember, most of our games were on desktop or laptops at that point, inside the Facebook platform. In India, the broadband usage graph and the mobile data graph hadn’t crossed yet; the Jio moment happened only in 2016. So, only the most well-to-do Indians were playing games—anybody who could afford a broadband connection and had a laptop or desktop at home. It was a very different type of usage.

One of India’s biggest industrialists used to play Zynga Poker a lot. He played so much that Zynga Poker had an auto-logoff feature. If we noticed somebody playing nonstop for 20-plus hours, they would get logged out because it looked like suspicious activity. This gentleman’s account was frozen. He actually sent his secretary to our studio in Bangalore to get his Zynga Poker account unlocked. We weren’t even running Zynga Poker from India at that time, but it was very interesting. That showed me the “whales,” as we call them in gaming—people who spend a lot of time and money and are hardcore players. There were a few of them. I know people who played Mafia Wars and Vampire Wars like crazy. Every now and then, people who are now in their twenties or thirties who were younger back then will say, “I played that game. I used to play it four hours a day; it was my life. My mafia clan was a big deal”. It always brings me joy when those conversations happen.

D: You mentioned the Play Store had just started. What was so exciting about it that made you leave Zynga and start your own studio (Tiny Mogul Games)?

A: I left Zynga in early 2013. The signs were very clear to me that India’s consumer market was waking up. Mobile phone sales were insane. Even though data was costly, we knew more mobile data usage would happen. We just never realized how fast that would happen once Jio launched, but it was expected. At this time, Motorola was still big, and Max was a big one, along with other Chinese OEMs. Windows was still trying to make the Windows phone, and Blackberry still had its own app store and ecosystem. But the Google Play Store had really taken off. I had been an Android user for a couple of years and could clearly see this was a thing. I could see the average Joe on the street moving to this. You could see that if we could break the $100 barrier on smartphones with half a GB or 1 GB of RAM—which was more than enough then—it would take off.

D: So what was the thesis for your new studio, Tiny Mogul Games?

A: The hunch was pretty strong that now would be a good time. When we started the studio, we had a five-year projection, but you build castles in the air, knowing a lot of things have to come true. Data has to become cheaper, mobile phones have to become cheaper and better, and their RAM and storage have to increase. Remember, storage was low then, which meant you couldn’t have too many apps. In fact, the most popular apps in the early years were the cleanup apps that deleted your cache.

But it was also clear that a country headed towards 1.2 billion people would play games. The fact that people would play their very first games on a mobile phone was becoming very clear. It had happened in Europe and the US; it was going to happen in Asia. Tencent had started thinking about games in a big way. All those things pointed to the fact that a homegrown game studio in India could make games for the Indian market, and maybe the global market, but with very Indian themes. That has been a theme in my thinking: there is a way of telling new stories with old Indian themes in meaningful ways, whether in television, movies, games, or books.

D: You mentioned Indian themes. Was the idea to export Indian culture?

A: My next theory was that we have done a very poor job of exporting our culture. South Korea does a phenomenal job; K-pop and K-dramas rule the world. We are mistaken when we think that Bollywood or Indian movies matter globally. They don’t, sadly. The Indian diaspora is very big, so if you have Indian friends, they make you watch a Shah Rukh movie, but Netflix still doesn’t have a single Indian global hit.

So the theory at that time was, could we build something that would make games for India, and then maybe eventually take them global?. Surprisingly, the global thing happened pretty fast. We got featured by the Google Play Store on its first anniversary at the end of 2013. Shiva, one of our first games, got featured globally. Suddenly, we had more downloads from outside India than from India, which felt very weird. This was the first Indian product to be featured globally.

Remember, the Play Store was a very small team then. The editorial team was literally one person sitting and looking at every app and game, and they would reach out to developers. There was no one you could reach out to; the editorial team would reach out to you. We didn’t even know what it meant to get featured—to have the Play Store’s homepage taken over by a banner of your app. We hadn’t yet realized the distribution power of these platforms. Even at that time, it was clear to people at Google that India would become one of its largest download markets. We were featured just before Christmas and were kept on for three-plus weeks, until January 19th. It was millions of downloads at that time. It was quite nuts.

India’s Mobile Gold Rush

D: What did virality mean then? How many downloads were considered viral?

A: Remember, these were heavy games for that time, maybe 50 or 60 MB. In India, that meant you were paying for it, because data had a cost. You were paying per MB, not per GB. So if you download a 50 MB game, you essentially paid six or seven rupees. We realized that when we optimized our APK size, it had a huge impact. I remember one game where we quadrupled the downloads by halving its size from 30 MB down to 15 or 16 MB.

Because I came from Zynga, we were very particular about our metrics. We focused on day-one retention (D1): a day after you install and open the game, what percentage of users come back?. How many played one week later (D7)? What was your engagement—how much time are they spending, how many sessions do they have?. We were very particular about improving our D1 and D7 retention and focusing on engagement.

Games are competing for attention. Unlike utility apps, when you’re building a game, you’re competing for people’s free spare time. You are competing with hundreds of thousands, even millions, of other apps. Over 90% of all apps on any app store are games; you’re competing with all of them.

D: So if it wasn’t just about download numbers, how did you think about achieving virality?

A: Your competition is insane, so virality meant very different things. When a user puts in the effort to download and open your game, is your hook strong enough? Is your delight factor strong enough?. Our chief game designer, Anand, always made this point: the simplest, smallest action in the game has to be the most delightful thing. In Candy Crush, the most delightful thing is matching those three candies and seeing them explode. In first-person shooters, it’s that headshot. It’s these small dopamine hits from the simplest action.

Those were the things you did for virality. You wanted it to be a water cooler conversation. You wanted people to tell other people, “When I have five minutes to spare, I’m going to play Shiva,” which were our games. Getting a large number of downloads was fine, but we were very aware that if your retention was low, this is a leaky bucket; these people will disappear in no time. Retaining them, getting them to invite other people, making the gameplay cooperative, or letting them play against other people—those were key. We built quizzing games and music challenge games where you could challenge another person. Simultaneously, a whole bunch of real money gaming, Teen Patti, and poker games took off in India, and it was clear they had their own virality and strong network effects because they were competitive.

Reviews as Insights

D: In today’s world, the default login is a phone number and an OTP, which lets you identify and contact users. Back in 2013, how did you do user research? How did you even know who your users were?

A: It was a norm, but we did it in different ways. Gaming is very testing-heavy. You have your own internal testers, but you also play-test it with a lot of people. We would have open days at our studio in HSR Layout, and people would land up for snacks and to play our games and give feedback. But these were often elite gamers or other people building products, so not necessarily the right set of people to get insights from.

At that point, the Play Store, with its ratings and reviews, was actually a very good way of getting to know people and understanding what they thought. If someone gave you a five-star rating, you wanted to reach out and figure out what they really liked. If they gave you a one-star rating, you wanted to reach out to them and figure out what went wrong, what broke, or what part of the game wasn’t working.

At that scale, you have to do a mix of qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative is looking at your funnels: are people downloading, playing, and coming back?. Then you’re looking at Play Store data, ratings, and reviews to find bugs or mechanics that aren’t working. But just talking to users was a big part of it: going around, showing it to school kids, talking to older people, or being in a cab and handing your phone to the driver saying, “Just play this game and tell me what you think”. We did this, maybe not in the formalized way we do user research at Google with the best experts in the world, but we did a lot of usability tests and play tests. We would always listen to our most passionate users, who would write long emails, and we’d get on the phone with them to figure out what was working.

D: Discovering that ratings and reviews were such a key part of the ecosystem must have been a revelation. Did you change the app to actively nudge people to leave them?

A: Yes, eventually it became a bit of a hack as App Store Optimization (ASO) became a real thing starting around 2014. Just like SEO, you realized there is a huge difference between an app with a 4.2 rating and one with a 4.7 rating. It was very clear that having high ratings was important.

So you ask: at what point do you ask for a rating? After a successful or fun gameplay session?. Maybe the user has spent 10 minutes on your game or has come back three days in a row. This user must be happy; should we ask for a rating now?. It’s a constant game that every app developer in the market has done. Are you looking at that incoming data, reading the reviews, and seeing how the rating trend changes week over week?. How does the rating change on a particular APK? For example, app version 1.7 had certain ratings, but when you launched 1.8 and fixed a bug, how did the ratings and reviews change on that?. These things mattered a lot.

People used to give a lot more ratings and reviews back then because they really loved expressing their opinion about the products they were using. Now everyone has 200-plus apps, so they aren’t sitting and reviewing every app. Back then, you had 10 or 20 apps and you wanted the app developer to know, “I played your app, I played your game, and this is what I thought”.

D: You’re right, games feel like an extension of identity, not a simple utility. How big is this entertainment category?

A: Absolutely. This is not a utility; it’s not a “need-based” app on Maslow’s pyramid. It’s entertainment. But when people watch a movie, they talk about it; they go to Rotten Tomatoes and say, “I hated this” or “I loved this”. The same is true for games.

If you look at global revenue from different forms of entertainment, gaming is right up there. A lot of people mistakenly say movies or music is bigger; music is very small globally. Gaming is way bigger. When GTA 6 comes out next year, a bad launch would be just a billion dollars on the first weekend. A bad launch. An average launch would likely be between one or two billion dollars, maybe over $2 billion in the first three days. Can you imagine any movie doing a billion dollars in the first weekend?. There are very few movies that have made more than a billion dollars in their lifetime revenue. Sure, Avengers and Avatar have, but people don’t realize that gaming....

D: Why do you think gaming revenue is so much larger than film?

A: This is a game you’re going to spend a minimum of a hundred hours playing. The average movie ticket price in the US is $12-$14; even in India, it’s climbing to 500 rupees. A game is going to be 60, 70, or 80 USD, but for hundreds of hours of gameplay. At a per-hour level, it’s super cheap, and it’s going to take up a big chunk of my life, weeks of my life. There’s no comparison. The number of games globally that made a billion dollars-plus in their lifetime—like Candy Crush—their lifetime earnings are bigger than most movies will ever be. Gaming is insanely large.

D: I’ve observed that people’s attention spans are shrinking; they scroll reels in theaters, and directors seem to be making movies faster, like TikToks, to keep them engaged. But you’re saying gaming is an active engagement. How do you square these two trends?

A: I think there are different types of people, and even the same person seeks different levels of engagement. The doom-scrolling, infinite-scroll, 15-second video is a very specific type of low-level engagement where your consciousness can recede to the background.

Whereas reading a book... did you realize book sales have never been better?. More long-form books are sold now than ever before. And look at the popularity of podcasting as a medium. I’m a huge fan of Acquired; they have three or four-hour-long episodes, and people listen to them—maybe at 1.5x speed, but they listen. People listen to audiobooks now, which requires a very active engagement because you are imagining what the characters look like and feel like.

So, movie directors who are trying to “TikTok-ify” their long-form movies are not going to succeed. Look at the biggest hits: Oppenheimer. Is Oppenheimer TikTok-ified? No, it’s deliberately slow; it takes you really deep in. In each medium, the best products—both in box office return and in that people genuinely enjoyed them—are deep, immersive experiences.

While your individual Candy Crush session might be five minutes, my mom has been playing Candy Crush for 15 years. When her phone changes, she wants to ensure her progress doesn’t drop because she’s put in a lot of hard work and effort. That is multi-year engagement. Engagement has different formats, and long-form will always be a big part of our lives.

The Sports Bar on Your Phone

D: That brings us to Hotstar, where you worked on merging media and gaming, particularly with the “Watch and Play” feature for cricket. What was the story behind that?

A: The original team that built “Watch and Play” did it for the IPL (Indian Premier League) in 2018, before I joined. Their deep insight, and a beautifully put one, was that T20 cricket is still a pretty slow game—three and a half hours long. Each ball takes about 40 seconds on average. The fastest bowler in the world, in terms of completing his overs, is Ravindra Jadeja; it’s very difficult to insert ads in a Jadeja over. In everyone else’s over, you can show a quick ad at the bottom, and there are ads between overs.

The insight was that by 2018, post-Jio, most people were watching the game on their phones. We were a video-first country; I would say the only video-first country in the world from 2018-2023, because we’re the only country where data is cheaper than water. In 2018-2019, the average Jio user was using 11 GB of data a month. What do you do with 11 GB? You are watching videos: YouTube, Hotstar, etc..

The insight was that people are watching on their phones, but they’re not watching it throughout. A homemaker might have it on while cutting vegetables. Or you’re watching it standing in a Mumbai local, holding the phone in portrait mode, not landscape. Your surface area is 40% video at the top, and the remaining 60% is completely useless. What do you do with that remaining 60% of the screen?.

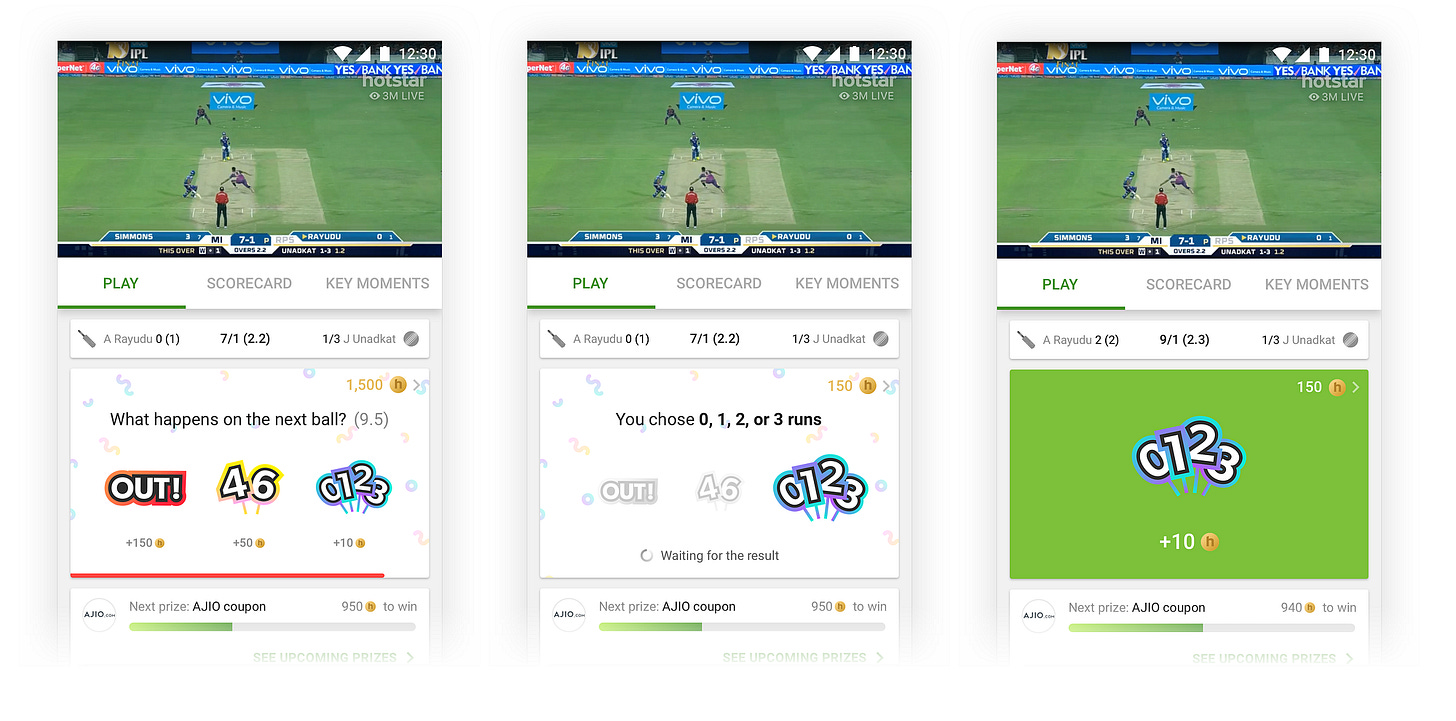

D: What was the solution for that empty space, and how did you evolve it?

A: People were not watching continuously. They would be checking the score on Cricinfo or other sites. When things heated up—like Dhoni coming out to bat—they would move over to Hotstar. People were actually watching these games in three or four-minute chunks. So, how do you keep them engaged during that time? More importantly, when an ad is playing, how do you stop them from dropping out?.

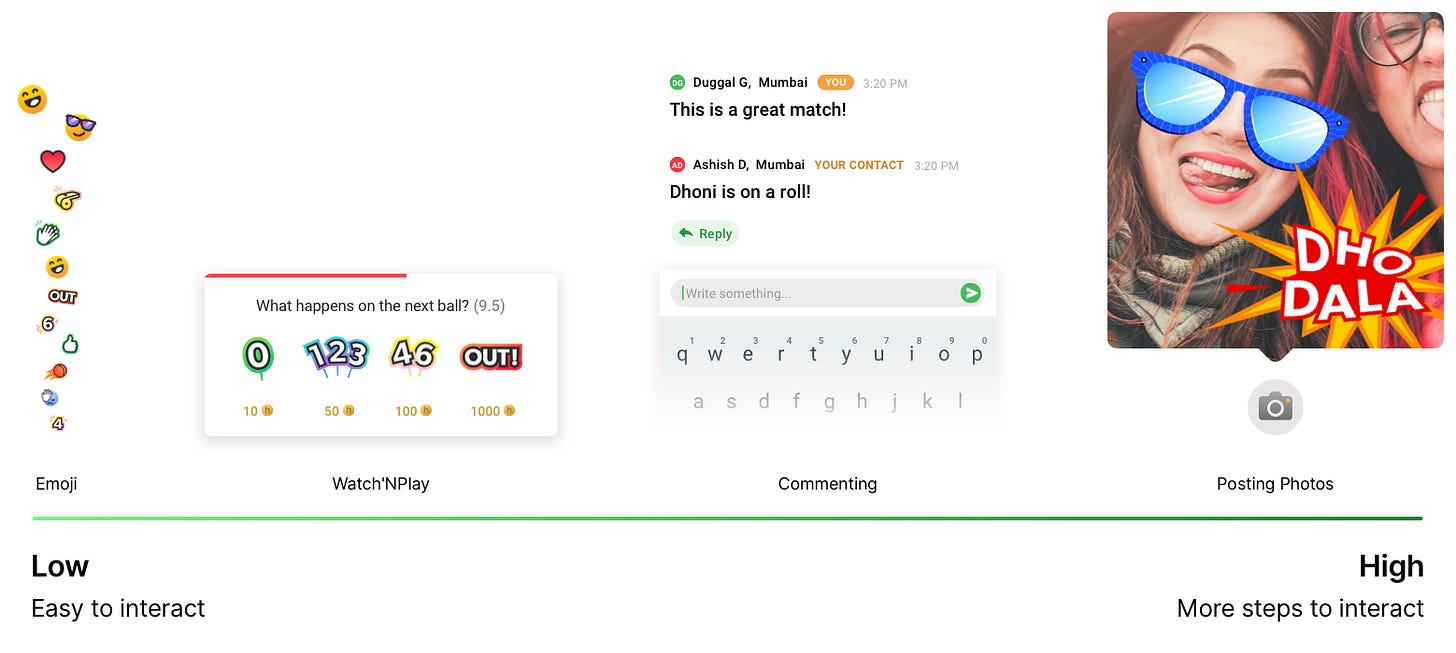

The other big insight was that everyone in India is an armchair critic: “That guy should have hit a six,” “He didn’t pull properly”. “Watch and Play” was born from this; it let people predict what would happen on the next ball. It was partly wishful thinking, partly predicting, but it kept them engaged so they wouldn’t drop off.

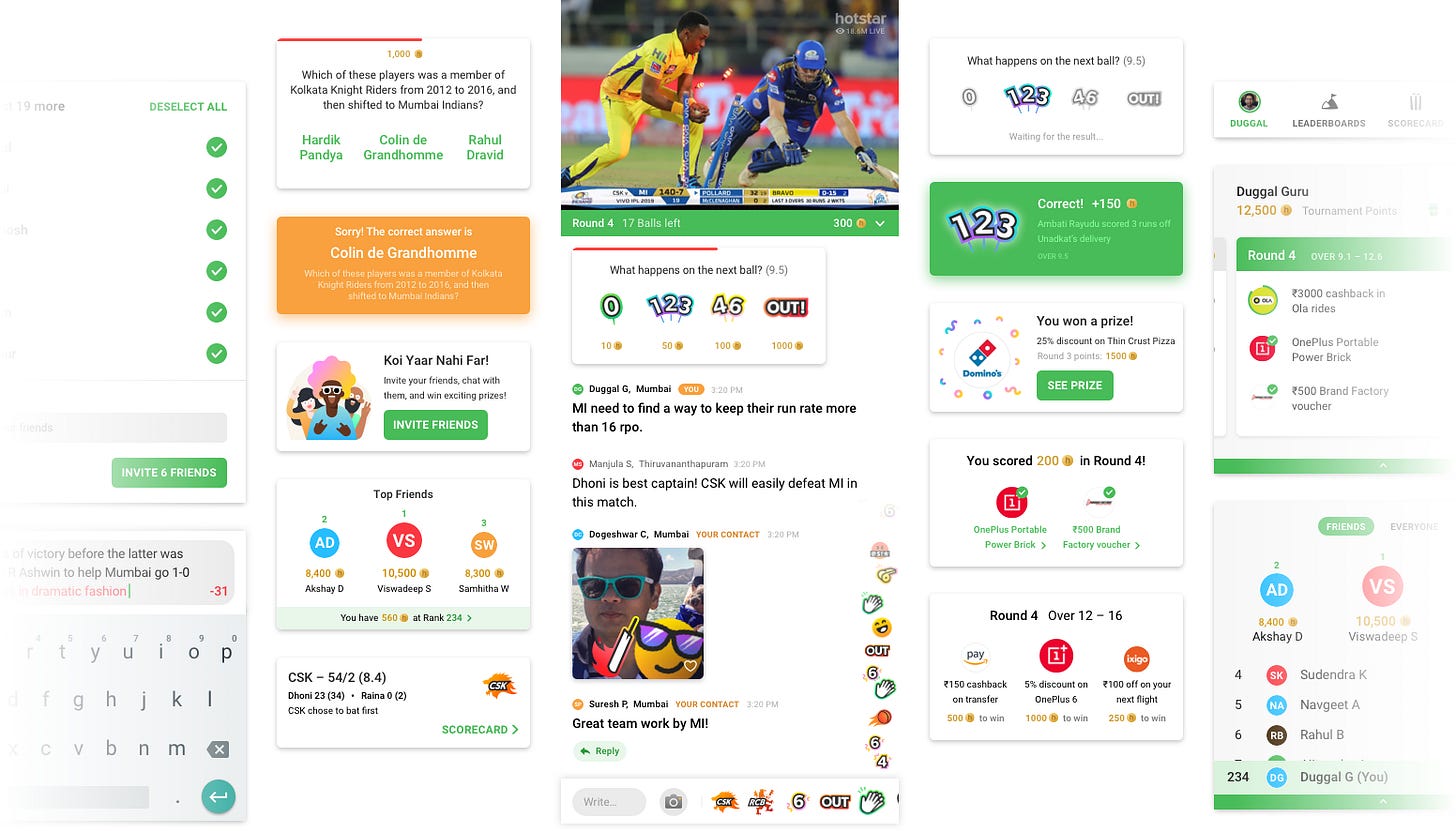

This is when we turned it into a social feed with emojis and the ability to chat with friends. Our whole thing was, when people skip out of the Hotstar app, they go to Twitter or Facebook to talk about the game. Why is this conversation happening on Twitter when it should be happening on Hotstar?.

When I came in after the 2018 IPL, we were prepping for the 2019 IPL and the Cricket World Cup. How do we take this to the next level and build the best cricket viewing experience?. The analogy I gave my team was that the best experience of watching live sport is sitting with friends at a sports bar: watching on a giant screen, cheering, wearing the jersey, and having friendly banter with fans at the next table. That’s the best possible experience. But not everyone can go to a sports bar; your friends are in different cities, or you’re commuting home from work. So how do you replicate that social engagement on a vertical mobile screen?.

D: With all this real-time data on voting and emojis, did it become a consumer insight tool for the show producers?

A: Oh, absolutely. We ran experiments for this, as Hotstar was part of the Star network. We were providing data: “Did people enjoy this episode? Did they like this new character?”. We would insert these surveys inside the Hotstar app. Also, episodes on Hotstar aired in the morning, whereas primetime was in the evening, so homemakers would have already seen that day’s episode. Real-time data could be provided to the writing and creative teams. For reality shows, it was very clear who people were voting for, and this early indicator could be shared with them.

It leads to very interesting things. I was also there when COVID hit and the stadiums were empty. The Star Sports team came to us and said, “How do we tell players that people are actually watching?”. We worked closely with them on the concept of a “fan wall”. We put giant LCD screens inside the empty stadiums to show live feeds of people from the Hotstar app, so players knew, “Millions of people are watching me play”. The emoji stream was aggregated and turned into sound effects in the stadium; all the stadium sound effects were powered from Hotstar. So in real-time, when Dhoni or Virat walked in and people sent billions of “I love Virat” emojis, we would aggregate all of them and use that as a signal to produce a sound effect in the stadium.

I still consider those two and a half, three years at Hotstar a purple patch; it was a small team that did wonders. Things have changed, of course. More Android TVs are being sold, broadband is becoming a real thing again, and watch time is moving towards television. So now there’s a real ability to build a second-screen experience: while you’re watching on TV, what are you doing on your phone?.

Every time I speak to friends who are in sports globally, they don’t understand this. Nobody has done this in soccer, the NBA, or the NFL. The level of engagement we built for the IPL and ICC is just insane.

D: As you said, Indian fan culture is very loud and expressive, whether in a theater or at a match. Was that what you were tapping into?

A: Exactly, which is why the theater experience and the sports bar experience is what I was trying to get to. Can we get people close to it?. We had asked people to connect using their phone book. So, for the example I gave of a friend walking into the bar and me waving at him, the equivalent on the phone was a notification. When you had connected your social graph, it would actually say, “Dharmesh Ba is now live and watching the game,” and you could literally send a wave. Then your chat would be visible only to you two. We built all these things because, why should all the social action happen on Twitter or Facebook?. It should happen here, within Hotstar. There should be no reason for anyone to leave Hotstar.

Delight in Payments

D: Finally, let’s talk about your move to Google Pay. It seems like a shift. In gaming and media, you’re interpreting user wants. In payments, if 10 rupees fails to send, the user is furious. How did you see this shift in problem-solving?

A: I no longer work on the Google Pay India app; for the last two years, I’ve looked after Southeast Asia. But I worked on Google Pay India for the first three years at Google and loved working on that app. It’s become such a key part of India’s data story and commerce story. I love it when in any movie, a hero says, “Just GPay it to me”. It’s become a verb, just like Google became a verb. I remember in one of Rajinikanth’s previous movies, he just tells the guy to GPay it to him. I was like, “Wow, that was the moment of like, we’ve made it”.

D: But you are right, the user needs are different. How do you reconcile that?

A: You are absolutely right. I’ve spent time in games, education, healthcare, and financial services. The problems are obviously different, but surprisingly, the solutions and the way you think about them are very similar. What is different is the hierarchy of user needs.

In most products, the first thing you must solve for is functionality: does it get the job done?. “Was I able to send 10 rupees?”. The second layer is reliability: can I do this reliably, again and again?. Payments infrastructure is a very complex thing—there are banks, UPI, and multiple providers—so failures happen. This is a basic need. If I send a sheep in Farmville and it doesn’t arrive, it’s not the end of the world. But if I’m standing in line buying medicine, I have to be able to show that blue tick to the guy so the next person in line can pay. So functionality and reliability become huge, huge barriers.

But I’d add, when the cricket stream went down at Hotstar, the brickbats we got in India were insane. “I’m watching the IPL and my Hotstar app is not working.” We would get lambasted. My video stream should not stop working. The problem is to solve for what people care about most, and that thing should not go down.

The wonderful thing I found when I joined GPay was that this was a team that was obviously obsessed with functionality and reliability, but they were also obsessed with the third and fourth layers: usability (Is the product actually usable? Is it easy to use?) and delight.

D: It’s rare to hear “delight” and “payments app” in the same sentence. Where did you see that?

A: There were so many small moments of delight baked into a payments app. That was one of the biggest reasons I joined GPay; here was a team running a payments product that was so obsessed with usability and delight. In gaming, usability and delight are the most important things. A game is not “functional” in that sense, but it has to be usable. Games are designed for the best usability experience. And then delight—every small moment has to be a moment of delight.

I came from a world where usability and delight were very high on my mind, and I loved that this team’s attitude was, “Payments is dull and boring, but we will build a delightful product”. That scratch card, which was a big deal; that blue tick emerging to give you a huge sense of relief that your payment has gone through; the sound effect; the fact you could add stickers or send a “packet” of money—these were beautiful small touches, small delights. You would get rewarded at the end of a payment with a voucher or a scratch card. I still love the fact that this is a PM, design, and engineering team that very openly talks about adding delight.

The bar for what is a minimum viable product has gone much, much higher. The win for anybody who has worked on usability and delight is that these have become part of the bottom layer, as important as functionality and reliability.

AI’s Next Frontier

D: We’ve seen these waves before—the App Store, then streaming video. Now we are in the AI wave. What do you think will change, especially for India?

A: I want to preface this by saying AI and machine learning have been in products for a long time; the amount of ML we used at Hotstar was insane. Generative AI is having a moment from a user perspective. For example, generative AI gives us the ability, if I am a Shubman Gill fan, to take a picture with Shubman Gill. I don’t have to stand in a line for an autograph; I can feel the joy of standing next to him at Wankhede. These are small, delightful experiences, but they matter. Generative AI can help build an experiential layer that did not exist before and will push the barrier for a viable product incredibly high.

Something I’ve been talking about recently is the “early sins” of generative AI: it has been very focused on “ask” versus “do”. Right now, all of GenAI is like a chatbot. You ask it something, and it gives you an answer. A tenth of the world’s population is using that, which is great, but I don’t think that’s how the next 30-40% of the world will interact with it. The “do” variety is when I’ve learned something, and now I’m asking you to do something for me: “Create this image,” “Write this thing,” or “Take care of this workflow for me”. Surprisingly, a very small chunk of people are actually doing the “do” part.

D: That’s an interesting distinction. Can you give an example of evolving an “ask” app to a “do” app?

A: It’s strange because all our functional utility apps are “do” apps: ordering food, e-commerce, ride-hailing. These are action-based apps; you do something, you don’t “ask”. I feel the next big breakthrough, especially for designers and PMs, is to take regular everyday products and figure out how generative AI can play a critical role in that “do” part. How will functionality, reliability, and usability change as a result?.

It could be as simple as recommending a new restaurant based on my food ordering behavior. This could have been done earlier, but GenAI can do it in a very different way. I could now have a “do” conversation: “It’s raining outside, I’m in the mood for chai and pakoras”. The agent knows my payment instruments and which restaurants I like. “Can you get me chai from Chai Point and pakoras from India Snack House, package it in one thing, send it to me, and just tell me I spent 72 rupees?”. Maybe it acts as an agent on my behalf and gets the payment done with one click.

These “agent-ic” flows... we have not even started scratching the surface. The next frontier is AI as your copilot, as your agent, doing things for you without taking away your joy of doing things. That’s a huge frontier to overcome. This is a wonderful time for PMs and designers. You are right; the world has been very deterministic. A leads to B leads to C. Now, A could lead to Gamma.

D: But isn’t there a risk of using AI for things that don’t need it?

A: You still have to solve a fundamental user problem, and you have to do it well, reliably, and in a usable way. A lot of people say, “But why do it using GenAI if your user metrics aren’t going to change?”. Absolutely. But when somebody does do it really well, it’s going to disrupt your business in such a big way that there are no sacred cows here. It’s not like people won’t change. If “agentic e-commerce” takes off, the e-commerce guys are going to have a real wake-up call. This is just the reality. AI is this very big shift, and there will be an early mover’s advantage here in a big way.

If you liked this essay, consider sharing with a friend or a colleague that may enjoy it too. (If you share on socials, tag me. I’m on Twitter (X) and LinkedIn)

The Google Pay delight layering you discussed is what seperates successful products from functional ones. That scratch card and blue tick sound effect are tiny details but they transformed payments from a utility into an experience. Your point about the shift from ask to do in agentic AI is spot on for Alphabet's future. If Google can build agent flows that handle complex tasks like your chai and pakora example, it could redefine how we interact with their entire product suite.

Super insightful conversation and really great questions! Thanks a lot for sharing this 🙌