The China Playbook Indian Founders Haven't Read

An interview with Alysha Lobo, Ex-Universal Robots & Rapyuta Robotics

Outside the newsletter, I run 1990 Research Labs - where I help global tech companies and Indian market leaders make sense of consumer India. If you’re navigating an Indian consumer bet, let’s talk.

I don’t remember the last time a meetup rewired how I think.

I showed up to a session by Alysha Lobo a few months backed organised by GrowthX knowing almost nothing about Chinese hardware. By the time she finished, I was dreaming of a trip to China. That’s the effect she has - her obsession becomes yours.

Alysha has a Master’s degree in English Literature. She can also program a collaborative robot in under 15 minutes. After eight years in robotics - Universal Robots, Rapyuta Robotics - she’s been exploring China’s hardware ecosystem firsthand and advising Indian founders on what they’re missing.

Her methodology to get information and connects are unconventional. She cold-emails Chinese CEOs. Shows up at their headquarters without appointments. Once, she got inside DJI because she stopped to pet a stranger’s Golden Retriever during a typhoon.

If you’re building in Indian hardware or robotics - or just curious why China’s manufacturing story matters - this conversation is dense with signal. She challenges assumptions Indian founders hold about Chinese competition, collaboration, and what “Made in China 2025” actually produced.

Alysha is the best example I know of “you can just do things.”

I hope you enjoy this as much as I did.

In this edition, we cover:

Why you cannot bet against the Chinese?

How WeChat replaced the App Store?

Why Chinese retail stores have influencer corners?

How Alysha got inside DJI without an appointment?

Why Chinese hardware competitors share the same lab?

How China turned a German acquisition into domestic dominance?

What chopsticks reveal about Chinese work ethic?

Which city cluster beat San Francisco in the tech rankings?

How Chinese gig apps protect workers from exhaustion?

Why Chinese youth are proud to take over family factories?

What is the current state of manufacturing in India?

Why you cannot bet against the Chinese?

Dharmesh Ba: Where did your love for robotics start, and why robotics?

Alysha: Oh, good question. I think I got into robotics accidentally. I want to be frank about that. I think there was a bit of serendipity. My dad would restore cars, and I have a love for all things mechanical. It’s been a great pleasure to be around my dad, who taught me the first love of machines: how machines move, how they operate. You know, we take so many things for granted. When you sit in a car, you jam the ignition, you’re hitting the brakes, you’re yelling at somebody, you’re slamming the door—without realizing that the ignition is made by a totally different company, the door you slam is made by somebody else, and the brakes are made by another. But all of these come together in a symphony to create a machine that eventually transports you from one place to another.

And for me, robots are just machines. I was very lucky when I was headhunted by Universal Robots. They’re considered the “Apple” of the robotics ecosystem. I think this was late 2016, early 2017. Initially, as I was in marketing and sales trying to scale up, I realized... you know, there are the engineers, and I’m not one. I have a Master’s degree in English Literature. So I was like, “I have no idea how this is going to work. How do you want me to work with robots?” And they said, “No, bring it. Bring me all of that experience, all of that skill that you have.”

What I’m grateful to Universal Robots for is that, as a marketing person, you do not get to sit in the office. You have to be out. You have to be in the field. You need to be going to customer sites, understanding how robots are used, and of course, be trained on the robot. So, one of my fun things I used to love to say—and I can still do it, by the way—is that I can train anybody to program a robot in under 15 minutes if it’s a collaborative robot.

Dharmesh Ba: I’m looking forward to it. What does a marketing and sales role for a robotics company look like?

Alysha: There’s a Hindi saying, “Jo dikhta hai wo bikta hai” (What is seen, sells). It totally applies in hardware. You cannot have a phenomenal hardware product and keep it where the sun doesn’t shine. There’s a reason you can go online and order an Apple phone or your Apple Watch. But the fun is when you go there, you experience it, you stand in front of it, and you look at this phone and realize, “Oh, it’s so beautifully made,” and it’s got aluminum and steel and all of these things combined together in a seamless experience. There’s a reason why phone companies invest so much money in experience centers.

So I think Universal Robots followed a very similar paradigm and philosophy. This is something I’m going to tell all hardware founders:

If you have a hardware product, you cannot keep it inside. You’ve got to take it out, you’ve got to let customers experience it, and you need to let it fail as well.

Because I think a lot of founders are very apprehensive, thinking, “Oh my God, if I take my hardware product out, it’s going to fail.” But it is bound to fail, and you have to keep that in mind. I think most people who will experience your product also have that understanding that this is hardware; this might fail.

Dharmesh Ba: How many times have you been to China?

Alysha: Lots of people who follow me on X [Twitter], and including when you’ve met me, think that I love China and that I’m absolutely fascinated with it. I am now. But the first time I went was in 2018, and I wanted to cry. I swore and I vowed that I was never going back to this country. I said, “This is terrible. They have smog. It’s dirty.” It was cleaner than India, but still. Nobody spoke any English.

And then - we’re obviously going to segue into this at some point—the entire Internet is in a bubble. It’s the “Great Firewall of Internet.” You have the Internet, but it’s China’s Internet. As long as you’re using their Wi-Fi, their apps, life moves seamlessly the way we have it here. But we, coming from the rest of the world, are used to a very different bubble. I cried because I just couldn’t get around anywhere. I had none of the apps (I was familiar with), I didn’t speak the language. I went on work with Universal Robots and would just land up working in the office for more hours than I should have because I said, “What’s the point? I can’t even get out.”

The person who inspired me was Adam Sobieski, the former General Manager for Universal Robots China. He was from the American Midwest—I think Minnesota—and he spoke fluent Chinese. In 2018, I made a commitment: “I have to go back. I’m going to learn Chinese. I am not going to let the Chinese get away with this!” That was my motivation. But when I came back, you just forget, right? I thought, “I’m never going back there. Why should I go through the trouble of learning the language?”

Just before we started this call, I was speaking with one of my best friends in the UK, and I mentioned a book that genuinely changed my life in 2020: “So Good They Can’t Ignore You.” I started reading it during the height of COVID.

At that time, everyone was furious at China because of the pandemic. But for me, two crucial lessons became clear. First, when you become genuinely obsessed with something, you inevitably get good at it. I thrive on getting obsessed and diving down rabbit holes. Second, I realized that regardless of global sentiment or who we blame for COVID, two facts about China remain absolute:

You cannot bet against them. Push them into a corner, and they will always come back stronger.

If you work in hardware, China is the Mecca. You simply cannot escape it.

I found someone offering Chinese classes on Twitter and started immediately, right in the middle of the pandemic. Everyone told me I was crazy. Since then, I’ve made two trips: the first lasted nearly a month in June (that was right after we met, actually), and the most recent was for about three weeks. I now plan to go and live there for a full month.

I’m incredibly proud that I still dedicate 60 minutes every single day to learning Chinese. This includes using Duolingo, brutally forcing my brain to remember the script, and consuming Chinese YouTube videos and podcasts. I’m proud to be able to speak the language, be on the ground, and experience China in a completely different light.

How WeChat replaced the App Store?

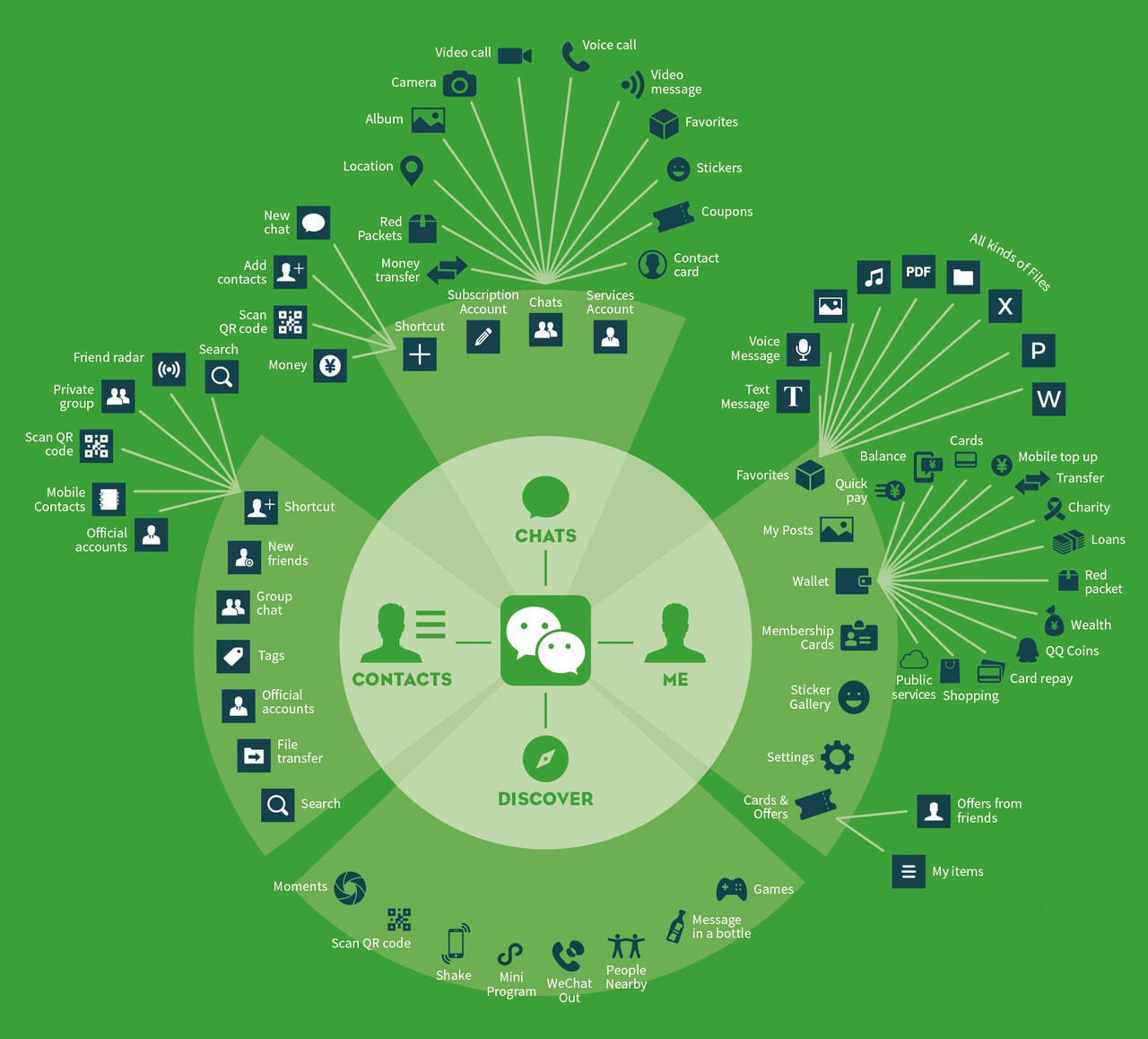

Dharmesh Ba: I have been in love with the WeChat ecosystem ever since I was introduced to it in 2019. How was your experience of using WeChat in China?

Alysha: I agree with that. Somebody was tweeting the other day, asking, “Why doesn’t India have a super app?” When you look at super apps, WeChat is definitely right on top. I honestly don’t think there’s any app globally - or definitely in India - that would fall into that category. I was talking to a dear friend about a week ago; he felt sick and wasn’t sure if he had COVID, so he stayed locked in his room. Everything was handled through WeChat. He ordered the COVID test, which was delivered to his home, and then connected to a doctor who diagnosed him and prescribed the medication right there on WeChat. The pharmacy even delivered the meds via the app.

Payments these days also happen via reading your palm. I don’t know whether I told you about it, but there’s no standalone app to book a robot taxi. You just go into WeChat, chat with the account, drop your location, and it sends you the robot taxi. I think what has happened in India and the rest of the world is we’ve siloed it out. You’ve got Paytm in India that did payments very specifically. They attempted to be a super app. I think Hike came up with messaging, but it was just a messenger. WhatsApp has tried to do it, but you can’t really go order groceries or get a cab on WhatsApp.

I’m not surprised you fell in love with WeChat. But as someone who uses it extensively now, sometimes it can be clunky. For example, on WhatsApp, you can long press to reply or swipe to reply. You can’t really do that in WeChat; you have to “quote” it. It is clunky.

I’m using it on Android, which is another joke because I have a Samsung S21 Ultra, and I still get judgmental looks in China like, “Oh, you’re a Samsung user?” Otherwise, I use an iPhone, which also gets looks like, “Oh, iPhone? You’re not using Huawei or Honor?” But yes, even booking a drone delivery for your food happens on WeChat.

Dharmesh Ba: So the idea of downloading an app on the Play Store or App Store is not the norm?

Alysha: Yeah, it’s not the norm. People just run their life on WeChat and Alipay. I’m addicted to Douyin (their TikTok). The only apps I use in the Western world are Twitter (X), and the rest of the time I’m addicted to my China phone - Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book) and Douyin. I love that they have a dedicated shopping tab. It’s very easy to scroll, and it feeds you stuff to buy 24/7. It’s amazing commercialization - E-comm, Quick-comm. For them, there is a very thin line between the two. If they say delivery is in 10 hours, expect it in eight.

You can go on Taobao or JD.com and have the equivalent of Amazon, but literally in an hour or two. I see Blinkit trying to do that now, saying “Hey, I can get you an iPhone or AirPods,” but this goes beyond that.

Why Chinese retail stores have influencer corners?

Dharmesh Ba: I remember you also mentioned that every major retail store has a dedicated section where influencers come and do TikToks. Can you talk about that?

Alysha: I think the East is a tad bit ahead of us regarding the future of work. One big aspect is content creation. For example, there is a German guy in Chongqing - one of the only 30 Germans living there - who has a bratwurst (A type of German sausage) restaurant. He said 50% of his time is standing outside with a tripod making videos to sell bratwurst on E-comm. When I went to a Xiaomi store, they were like, “Oh, you are a foreigner and you want to take videos? Please go ahead, we want you to be an influencer.”

Also, regarding retail stores: the variety is insane. You step into a car showroom like AITO (Chinese smart electric vehicle brand) you’ll see Huawei products because of their collaboration with Huawei. Same with Xiaomi - I can buy a toothbrush, a dental flosser, a pet home, a rice cooker, a car, a TV, and tires all in one place. The brands are trying to be almost a “super brand.”

How Alysha got inside DJI without an appointment?

Dharmesh Ba: Right. I wanted to talk deeper into that, but first: you mentioned you just cold email people and land up in their offices. What does that process look like?

Alysha: That is an Alysha special. I’m a third-culture kid - half European, half Indian, grew up in Saudi Arabia. I’ve learned that adaptability is an underrated skill. My parents taught me: Ask. What’s the worst that can happen? Somebody says no. But what if they say yes? With China specifically, I offer them a view of what’s outside the “Great Firewall.” I write to companies and say, “Hey, I’m coming. I don’t have an agenda, but I would love to learn about your product and tell you where I see it fitting in the rest of the world.” That really goes a long way.

Dharmesh Ba: What were your top favorite companies you wanted to visit? I know the DJI story, but who else was on the list?

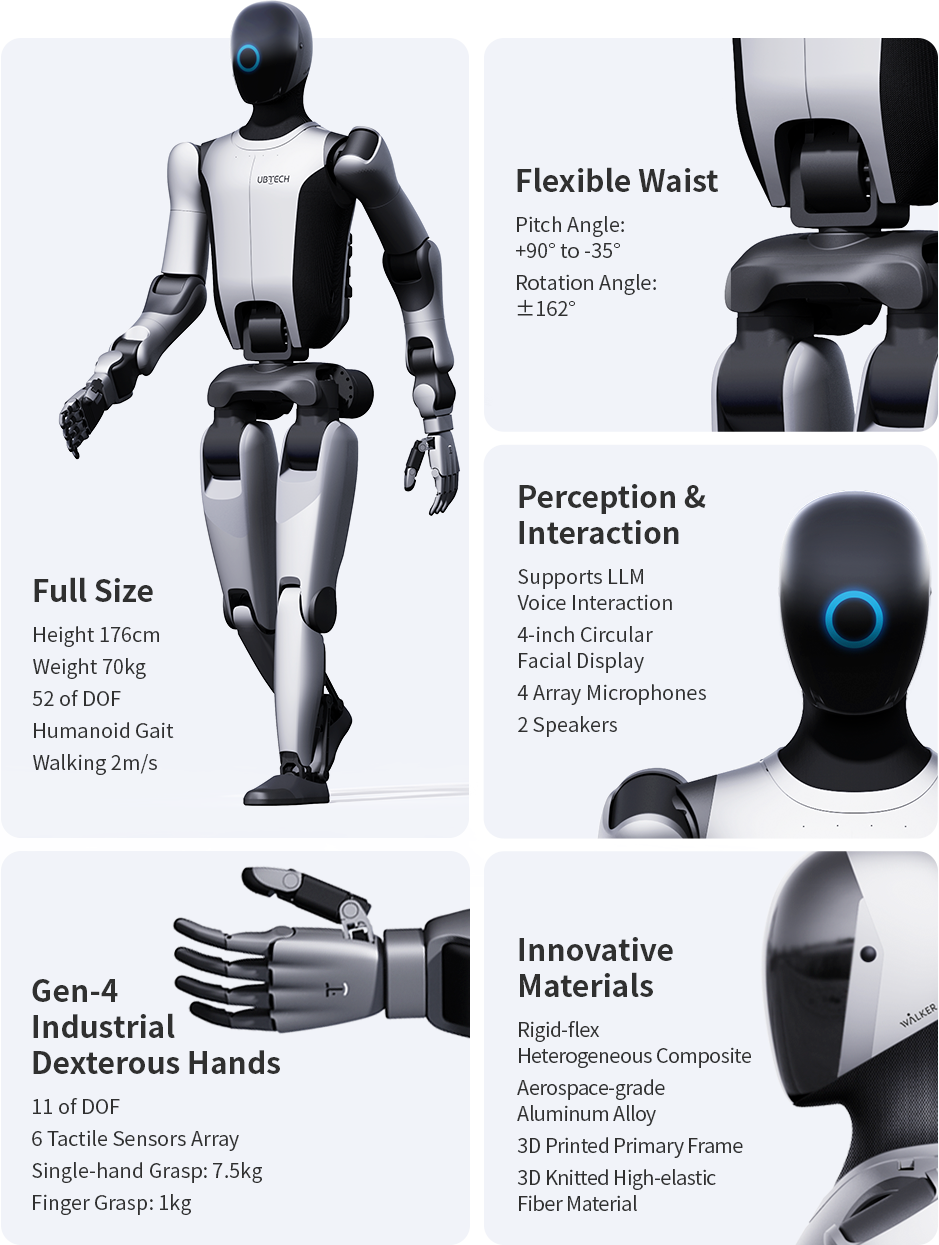

Alysha: I reached out to everyone - Alibaba, Tencent. Unitree Robotics out in Hangzhou - I’m grateful to have them on WhatsApp. LimX Dynamics (Limax) in Shenzhen - they were very open.

I wanted to get into UBTECH so bad. They have that cool robot, Walker, that can remove its own battery and put a new one in. I tried emailing, DMing - no luck. So when I was at LimX’s office, they said, “UBTECH is down the road, just go.” I kid you not, Dharmesh, their entire office looks like a spaceship. There is no reception, just an eye scanner. I stood outside, saw a lady on a call, and told her in Chinese, “Bu hao yisi” (Excuse me), I want to get inside. She scanned me in! I handed them my passport, and they left me unchaperoned inside.

UBTECH themselves loved it. They were like, “You just showed up? No appointment?” I said, “No, but I know about Walker, I know about your AMRs, I know about your partnership with BYD.” And they couldn’t say no.

Dharmesh Ba: I want this to be helpful for someone young who only thinks about ChatGPT or Gemini. Why should they think about robotics?

Alysha: Don’t listen to me; listen to Sam Altman. He said, “Even if we had the smartest brain right now, we just would not have the hardware to keep up with it.” Hardware is the other side of the AI coin. I use the Ferrari example: I can show you a shiny engine, but until I put it in a Ferrari and we hit the gas, you won’t experience it. Robotics is moving from the industrial space to your home. You have robots already - washing machines, mixer grinders. Now, machines are becoming intelligent. You see Pudu robots in restaurants. The truest experience of AI will come when combined with hardware.

How Alysha got inside DJI without an appointment?

Dharmesh Ba: Tell me how you landed in DJI without an appointment.

Alysha: That comes down to my love for dogs. I’m dying to make a thread on X of all the dogs I petted in Shanghai and Shenzhen. My standard line is “Ni hen piaoliang” (You’re so pretty) or “Ni hen ke’ai” (You’re so cute). I was in Shenzhen, and Typhoon Wutip was coming in. DJI hadn’t replied to me. I stumbled upon a square where 200 people were doing Zumba and ballroom dancing. I saw the fluffiest Golden Retriever. I asked the owner if she spoke English; she did. I missed my dog, so I asked to walk with them.

She invited me for watermelon at her place. Trust levels in China are insane. We’re eating watermelon, and I tell her I’m on a “truth-seeking journey” about China and hardware. She turns and says, “You really are on this truth-seeking journey. I work at DJI, and I will get you a pass inside.”

And I did. The building is entirely cantilevered. They have a drone testing lab suspended in the air. I couldn’t take pictures because the security QR code changes every five seconds. They are now talking about being “flying photographers,” not just a drone company. Moral of the story: You see a dog, go pet it.

How China turned a German acquisition into domestic dominance?

Dharmesh Ba: This evolution connects back to Made in China’s 2025 policy. What’s your take on that?

Launched in 2015, China’s “Made in China 2025” (MIC 2025) is a strategic policy to become a global high-tech manufacturing superpower by 2049, focusing on innovation and self-sufficiency in 10 key sectors (e.g., AI, robotics, EVs).

Alysha: I think it’s foresight. The right government policies can do so much. Let’s look at their foresight - if I’m not mistaken, both the Mayor of Shanghai and the Mayor of Shenzhen are engineers. Shenzhen itself is so well developed that you are not more than five minutes away from any metro station entrance. That entire trip in Shenzhen, I only took the metro. Because it was so easy for me to get around. I even took the metro to the airport because I could just take my stroller; it’s that friendly. The only thing is you’re fighting a bunch of these EV guys who are riding right beside you - that’s the only way I’d probably die in Shenzhen, by the way.

Just saying, back to policy and “Made in China 2025” - we really need to look at 2015. That was the landmark year when they decided, “Okay, we’re done being a mediocre manufacturing economy where we’re manufacturing stuff where we tell people...” You know, we used to have these jokes where if something broke, we’d say, “Yeah, it’s probably Made in China.” They wanted to get rid of that notion. So they came up with these policies and the 10 sectors.

Let me comment on one sector that I’m most familiar with: robotics. Why I put out that piece you mentioned was that they identified robotics as a sector they needed to get better in, while being fully cognizant of the fact that if they wanted to be a manufacturing economy, they also needed to have the right robotics in place. It’s a problem: “My current robotics companies are not up to the mark, but I also need robotics because I want to do manufacturing.”

They just went and bought one of the biggest European robotics companies. This was 2016 into 2017. I’ve written about the Midea acquisition. Think of Midea like a BPL or a Videocon of India - they made all these ACs and appliances. Midea went and bought the biggest robotics company, which was Kuka.

Now, when that happened, you’d think all the other domestic robotics companies would suffer because they brought in the “big European boy.” That didn’t happen. They continued to deploy Kuka, but they made sure to prioritize their own internal players. They said, “Okay, we’ll deploy Kuka, but we also want to see an Estun out there. We also want to see a SIASUN out there.” They told them, “This is not competition. This is for you to learn how to be a better robotics company.” And look at where we are today.

Dharmesh Ba: Where is the culture of collaborating and not competing come from in China? Its not the case in India.

Alysha: I was in a car - my friend’s car - the Avatr. The Avatr is not just a car. The Avatr is a combination of Changan Automobile working with Huawei, working with CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited), coming up with a joint car.

So, the spirit of competition, to a certain extent, is also nourished and foisted upon them by the government. There are two things here. One: you’ll see so many brands—robotics, humanoids, EVs—but ultimately, they will consolidate, and you will find only two or three major players. This is how China works. The government never lets anybody get too big that this consolidation doesn’t happen.

Two: the spirit of cooperation. Like Huawei saying, “I can’t build cars, but I would love to give you the software.” Because their ultimate goal is that now you’ll find more people who have Huawei cars having a Huawei phone. It pairs well. I see a similar trend with robot companies. Companies like Estun and others have learned from Kuka and bettered themselves. That doesn’t mean Kuka’s sales have dropped; their sales increased too, primarily because China is the customer.

For me, the fact that policy drives this—saying, “If you put robots in, I’m going to give you benefits”—is the kind of thinking we need in the rest of the world.

Chinese domestic companies are the biggest consumers of their own tech. I would love to see this in India. If Indian companies can prioritize Indian tech first—not just under the banner of “Make in India” or self-reliance, but because we owe it to our economy and the younger generation making things—it would do wonders for our startups.

Why Chinese hardware competitors share the same lab?

Dharmesh Ba: Yeah. This also trickles down to what you mentioned about maker spaces being more common, young folks getting in there early, and getting support from bigger companies. I found that very interesting. What was that about?

Alysha: This time, when I went to Shanghai, I had the good fortune of going to Zhangjiang AIsland (AI Harbor/Island). It’s the idea of compounding value by proximity. You have a lot of these robot companies clustered in the same place. You wouldn’t find that in India, or maybe San Francisco would be the next best example.

At this AI Island, they had a lab that was almost free of cost for their engineers to enter. It doesn’t matter which company you work for. You could be working at a rival robotics company, but your rival’s robot is right there in that lab. You walk in and you can try to build because they’re looking at hardware as a platform.

I love this. I think we need more maker spaces in the country. We have an absolutely fantastic lab in Bangalore called the CMTI (Central Manufacturing Technology Institute). I would highly urge people to check it out. I would love to see if we can open it to the public where people can come, tinker, and have access to machines—SPMs, VMCs, CNCs. When you make things and break things, that’s the only way you learn.

I would love to see more maker spaces—maybe a floor with 3D printers and machines where you can tinker. Imagine having access to your competitor’s robot. You should be scared, thinking, “What if they tear it apart? What if they see the flaw?” They’re not scared.

What chopsticks reveal about Chinese work ethic?

Dharmesh Ba: I think psychologically speaking, they’re confident and comfortable in their own shoes. In India, we are too focused on the competition rather than figuring out the best we can potentially do. To some extent, we have that “frog in the jar” mentality—you don’t need a lid if it’s Indian frogs.

Alysha: Don’t get me wrong, there is a deep sense of competition with the Chinese. But they realize some things are beyond their control. If somebody wanted to find a flaw in their robot, they could just buy it and tear it down. What’s stopping them? Finding OEMs there is not difficult. So, the focus is on continuous improvement.

Let me use an example here. They gifted me a set of chopsticks. When I was seeing my colleagues in June, they were making fun of me, saying my chopstick skills improved. I said, “Of course, I lived in Japan for three years.” The guy was quick to tell me, “Chinese chopsticks are different from Japanese.”

He explained the symbolism: Chinese chopsticks are often round at the eating end and square/sharp at the holding end. The symbolism is that the part facing outward (the round end) means I need to be kinder to you, and the part pointing toward me (the square end) means I need to be harder on myself. They gifted me a beautiful set of traditional Chinese chopsticks as a reminder. That is in their culture—they are very hard on themselves. Even regarding their high-speed rail, which is the best in the world, they feel they could have done better.

Which city cluster beat San Francisco in the tech rankings?

Dharmesh Ba: Interesting. You also mentioned people coming back from the US and wanting to contribute back to China, not just for opportunities but because they love the energy.

Alysha: I myself am planning to take an apartment there and live there for a while. This is coming from someone who has lived in New York, Chicago, Tokyo, Copenhagen, Dubai, and Bangalore. I see more and more people packing their bags from the West and moving back. China is not imitating anymore; they are innovating.

This year, WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) declared that the Shenzhen-Guangzhou-Hong Kong cluster is the number one science and technology cluster in the world.

Guess who’s second? Tokyo-Yokohama. Number three is San Francisco. We all think SF is number one, but it’s not.

I think many people are scared to go to China because of the rhetoric. But the facilities are amazing. I fell sick in China—I went to the ER. Do you know what my bill was? 750 Indian Rupees with medication.

Dharmesh Ba: Wow. Never once asked for insurance?

Alysha: No. I even forgot my passport. I fainted in the metro, and the police helped me. I went to the Peking University Shenzhen Hospital. They triaged me effectively. When I got to the ER room, I got a young doctor who spoke English with a thick Australian or New Zealand accent—so he studied there and came back.

They didn’t over-medicate me. The bill was 650-750 rupees. No insurance questions, no six-week wait times. Even for my blood pressure monitoring, they told me I could walk into any pharmacy—traditional or modern—and use the high-tech BP machines for free. Why would I not want to live in a place like that?

Education levels aren’t falling either. Companies like Unitree and Deep Robotics came out of universities in Hangzhou, like Zhejiang University. Tsinghua University is equal to MIT there.

Why Chinese youth are proud to take over family factories?

Dharmesh Ba: You also spoke about how they take pride in what they do. You mentioned a girl trying to help her dad’s fabric business by going abroad and coming back.

Alysha: Yes, I met her at the airport while sharing a plug point. She was on her way to France, Germany, and Amsterdam to learn the latest fashion trends. Her parents make gowns—the kind you see on Myntra. She said, “What better way? I would rather learn from there, come back, and manufacture that here.”

She was proud to take over her parents’ business. I’m seeing this in India too—younger people taking over manufacturing businesses. It goes beyond the Shanzhai (copycat) culture. They want to innovate.

How Chinese gig apps protect workers from exhaustion?

Dharmesh Ba: That was very beautiful—harmony between new technology and older ways. You also spoke about how they aren’t afraid of automation, and how gig workers get locked out if they overwork.

Alysha: Yes, this was the Ele.me and Meituan riders in Chongqing. Chongqing has difficult terrain. The delivery drivers have a clock; if exhaustion sets in, the app locks them out. It’s a kind way of doing things. There is dignity in gig work. I see a lot of women delivering too.

Regarding automation: I used to fight this battle eight years ago. People said, “Robots will take our jobs.” I compare automation to ATMs. Did banks shut down? No, more people started banking. Automation takes away non-essential tasks.

The idea of a “lights-out factory” (fully automated) is still partly a utopia. Peak production still uses humans. I went to BYD North; they had a huge notice board hiring for CNC operators and automation engineers. Humans still work alongside robots.

I also noticed in China and Japan, people are wired not to ask for free money. They will work, fish, or find ways to earn rather than beg. I have a mental picture of a road sweeper machine working alongside a lady with a traditional bamboo hat using a picker. It’s a symphony—everyone doing what they have to do to better the country.

Dharmesh Ba: I have a thesis that every generation’s expectations quadruple. We will always have automation taking care of old chores to open up capacity for new expectations.

Alysha: I highly recommend reading The Rise of the Robots by Martin Ford. With every industrial revolution, we’ve had a churn of jobs. We are talking about the Fifth Industrial Revolution. Expectations have changed, but so has the pressure. Pervasiveness of technology is only going to get more interesting.

What is the current state of manufacturing in India?

Dharmesh Ba: What’s the state of manufacturing in India, and why is there a gap in collaboration?

Alysha: We are price-sensitive in the manufacturing sector. While good, the government should reward companies for using Indian automation. Currently, they get more value for money bringing robots from China. China learned by bringing machines from Germany and Japan, and now they make them better.

There is a disservice being done to our startups when local manufacturers prefer Chinese tech due to price. Startups only get better if they get iterative feedback. I see Hubli and Belgaum (Tier 2 cities) actually being more excited about adopting local tech than some metros.

Dharmesh Ba: For a hardware or robotics founder facing barriers in India, can you give some positive pointers?

Alysha: India is waking up to the fact that we can be a manufacturing powerhouse. Jensen Huang (NVIDIA) said we pegged ourselves too much on software, which will get automated. We are culturally and economically closer to China than we think. We should ride the tailwinds of geopolitical shifts.

This is a great time for startups in robots, drones, and old-school manufacturing. We have a great layer of System Integrators in India that is ignored. In the US and Europe, System Integrators are crucial; China does it themselves. We should leverage our System Integrators.

I’m very bullish. My personal angel investments are in Indian robotics companies. I’m happy to chat with startups, large corporates, or anyone wanting to get into hardware. If you’re non-technical but want to work in robotics—sales, operations—we need you. If you’re afraid to leap from SaaS to “HaaS” (Hardware as a Service), you won’t regret it. My DMs are open on LinkedIn and Twitter.

Alysha Lobo runs a fantastic newsletter on robotics, hardware and Indian manufacturing which I highly recommend.

You can ping Alysha on X (Twitter) and LinkedIn.

If you liked this essay, consider sharing with a friend or a colleague that may enjoy it too. (If you share on socials, tag me. I’m on Twitter (X) and LinkedIn)

Loved this! Such a beautiful snapshot of the life these days in China. And so many good reminders ( like "Just Ask" - of course!).

the point about 'compounding value by proximity' reminds me of a recent read on on Xiaomi’s supply chain (One inch ahead - https://open.substack.com/pub/howardyu/p/how-xiaomi-came-back-from-the-dead?r=49n3h7&selection=c664362b-1e43-4377-b9f8-1509e7c0fffa). That ability to iterate hardware rapidly because your supplier is next door (the cluster effect) is an advantage we definitely lack here.

Also thanks for the CMTI shoutout - definitely looking them, up

WeChat was the main inspiration behind Hike.

But WhatsApp simply had superior network effects and it could never reach retention levels where WeChat like services could become viable.